Build homes not prisons

Build homes not prisons

Prisons punish people while directing essential resources away from communities. A single prison space costs approximately €100,000 annually. This money could instead help communities flourish. Community, youth and voluntary services were devastated by austerity and stretched further by the Pandemic. Despite constantly struggling for funding, they provide essential educational, health, employment and other supports that make lasting differences in the lives of criminal punishment impacting people and communities. Reducing social harms, creating genuine safety, and moving away from prisons that do not work, demands strong, resourced communities. Re-allocating resources to communities, means they must have a real say in how funding is used. Services that prioritise access, equality and local relevance benefit everyone.

Invest in communities

We need a community development approach whereby community members are actively involved in deciding on the services and supports needed in their own communities. Financial resources must be diverted away from outdated, ineffective and damaging punitive systems, into comprehensive state funding for community development and youth work. Resources must flow from the top down; from the state to local communities. But decisions about priorities and needs must come from the bottom-up. They cannot be imposed via a one-size-fits-all model, at either the local or national levels.

When allocating resources to communities, they should have a real say in how the funding is used. In addition to supporting mutual aid approaches to community building and care, participatory budgeting methods can be employed. They would allow local communities who are experts in their needs, have direct involvement and agency in deciding how funding is re-invested based on local needs.

The relationship between social and economic inequality and rates of violence within society needs to be addressed and we make communities safer by tackling inequality. Austerity ravaged community development and youth provision between 2008 and 2015. But recent governments have also used funding relationships to impose new conditions and top-down agendas on community and voluntary sector organisations. Funding should not be tied to a criminal justice approach.

President Michael D Higgins, stated that Ireland is experiencing not just a housing crisis but a “housing disaster.” “Law and order” rhetoric continues to be used as a diversion from the scale of housing distress across the island, whereby record numbers of children, adults and families are dependent on emergency accommodation for a place to live. Bolstering prison infrastructures consumes land, logistics, funding and resources that should be diverted into the building of homes. This is an immediate and urgent priority.

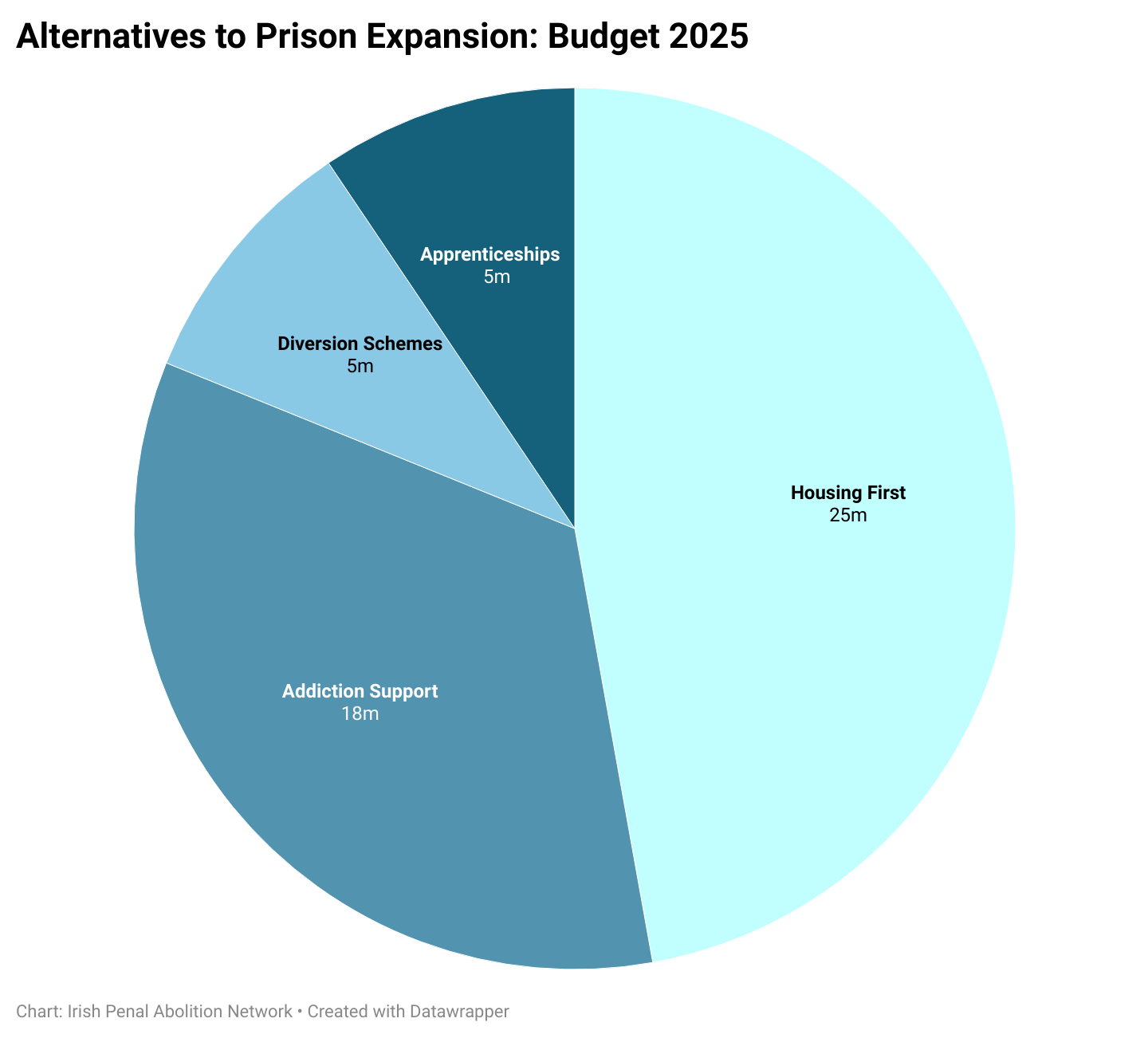

A reallocation of the €53 million committed in Budget 2025 for capital funding for prison expansion could be spent in ways which would strengthen communities and impact individuals most at risk of contact with our systems of punishment (see graph below). Spending an additional€25 million on Housing First would increase its 2024 allocation by over two-thirds. While €18 million could provide 5-week residential placement, 10-week outpatient placement, and 24 months of continuing care for up to 1,000 people. An additional €5 million would provide 500 annual apprenticeships with the remaining €5 million committed to diversion programmes. There are many more creative, and efficacious, uses of our taxes than more prisons.

Across Ireland, urban, suburban, rural, small-town and village communities feel forgotten-about and vulnerable to crime. Instead of punishing after something happens, we assert the need for strong local infrastructure that actively counters isolation, stigmatisation and exclusion and to create conditions where people are safer. So-called “law and order” responses exacerbate social anxiety. They spread distrust and insecurity, while doing nothing to address the causes of social harms – the true threats to safety. As a first step, essential community services, such as post-offices, community centres and local shops should be supported to keep open. They are crucial for reversing the isolation and feelings of insecurity of people who are living alone, or in under-resourced or remote areas.

The level of addiction and the inadequacy of associated health, counselling and psychological supports leave many families and communities across Ireland bereft. Policy makers and politicians need to recognise the complete dearth of recovery support in rural areas, towns and economically oppressed urban areas. We should tackle addiction as a public health issue rather than a criminal justice issue.

Prison cannot be the fix all in the absence of other support. Particularly for people who are experiencing mental ill health or psychological distress, and are over-represented within prison populations. Rather than investing in prisons, we can prioritise investment in mental health services. This means addressing the waiting lists, staff shortages, the lack of cooperation and communication across services, and the poor quality of facilities that have been highlighted by the Mental Health Commission and the Ombudsman for Children. Government must respond to “crimes of misery” by means other than punishment. This means the Government should require local authorities to practically recognise the hardships faced by people living in poverty, who are homeless, addicted, mentally ill and on the streets. People should never be punished for having to resort to begging, sleeping, washing, defecating, etc. in public places, simply because they do not have access to adequate accommodation, basic amenities and critical supports.