A Cry for Life and Political Care; From Beneath the Ashes Fallen Upon Us

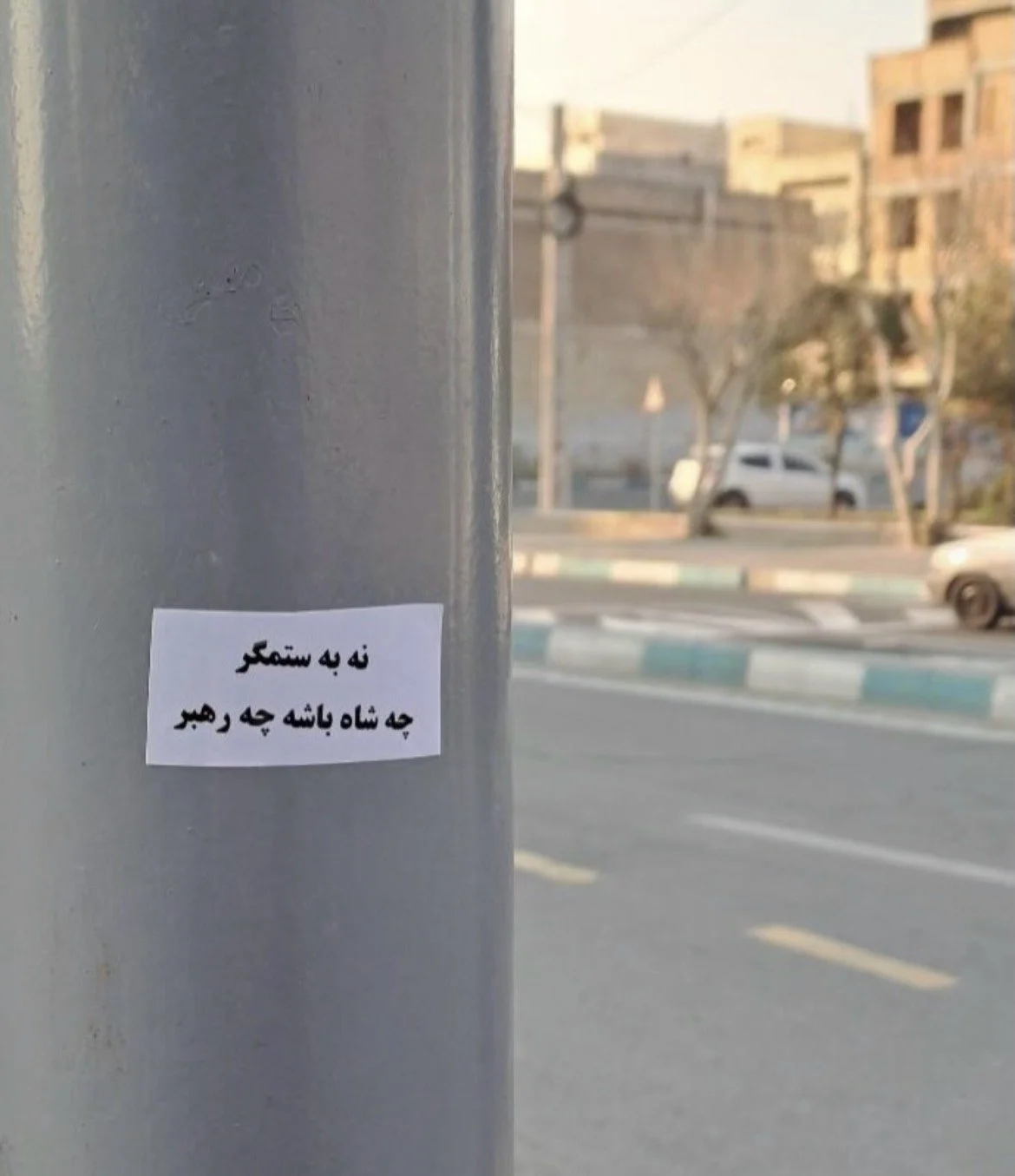

A sticker on the street of Tehran which translates as “No to the oppressor, whether a king or a leader.“

By Neda Naji

In the aftermath of the 1979 Iranian revolution, the newly established Islamic Republic seized the apparatus of the Iranian state, including the Shah’s prison apparatus, SAVAK, and brutally imposed a renewed order of intimidation and torture. It carved deep and lasting wounds into the bodies and psyches of political prisoners, wounds that survivors continue to carry across decades. Repression was, however, never confined to killing alone. Massacres, mass arrests, and the issuance of death sentences operate as interconnected components of a single machinery, one that disregards even the regime’s own inhumane juridical frameworks. This recurring cycle constitutes the repressive logic of the Islamic Republic as a totalitarian formation, at times articulated as revenge and at others as the calculated production of terror.

Today that logic has been reactivated in its fullest capacity. The state has mobilised all its repressive force, summoning loyalists into the streets, enforcing internet blackouts, and sealing the circulation of news and testimony.

Prisons and the imprisoned in Iran

We now confront a catastrophe whose magnitude recalls the darkest scenes of the 1980s, most forcefully the summer of 1988, when even prisoners serving fixed sentences, some only months away from release, were sent to execution. Under conditions where prisons cannot be monitored and where the Prisons Organisation stands complicit rather than protective, urgent attention must turn to former prisoners and those detained in the recent uprising, held across prisons, detention centres, safe houses, and undisclosed black sites.

The figures reported for the number of those killed are beyond comprehension, truly horrific. We are all in mourning, staring in disbelief at what lies before us. Amid communications blackouts and fragmentary reports, arrests continue to expand. Officials repeatedly invoke the charge of moharebeh, translated as “enmity against God”, a charge whose sentence is death.

The widespread protests that erupted at the end of 2017 and at the end of 2019 in response to economic injustice, rising living costs, unemployment, poverty, and structural inequality, and which began in marginalised areas, marked a clear moment of political transformation in Iran’s social struggle. Previously, despite legal ambiguity, the intersubjective recognition of “political prisoners” had been possible, but that boundary has now collapsed. Since January 2018, both among those detained and those killed, there have been individuals whose lives, without engagement in political activity as formally defined, became entangled with politics and who acted to transform it. This pattern continues in 2025. Many individuals similar to those arrested in 2017 and 2019 are not recognised as political prisoners, neither by themselves nor by segments of society, leaving them without any system of care or support both during detention and after release.

Yet the form of detention that the Islamic Republic has initiated following the repression and killings in the streets is not a response to “crime”, but a response to the increasing politicisation of everyday life. Security forces are raiding homes and schools, detaining a wide range of citizens, often simply for the potential to dissent. Similar patterns appeared after the 2017 and 2019 protests and the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, but this time the scale of arrests and accompanying massacres is staggering. Whilst it is understandable that confronting the reality of this blood-soaked atmosphere leaves us exhausted, the narratives of the living must be heard.

Access to media is severely restricted, especially under the current internet blackout. Families gather outside prisons, facing humiliation and harassment, seeking any information about their imprisoned loved ones. Courts accelerate proceedings, sometimes issuing death sentences just days after arrest. Detainees are pressured, tortured, and forced to confess or sign blank documents without access to legal counsel, putting them in grave danger. Prisoners in facilities such as Qarchak, and in even worse conditions, are held in unbearable environments with little chance of having their presence or voices recognised. The killing of protesters, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, torture, sexual violence, and widespread executions have become normalised and institutionalised tools of governance. In this system, the state assumes not only the right to punish but also the authority to decide over life and death.

Beyond Anger: the potential of Abolitionist Feminism

It is therefore unsurprising that in response to such oppression, public anger intensifies, and revenge appears as the only adequate response. The key question is not whether anger is legitimate, but where it is directed and what kind of order it produces. Theory and generalizations lacking immediate, actionable strategies struggle to penetrate this atmosphere of raw anger and confrontation. In this context, anger is not excessive, but an intelligible response to injustice and death. Yet if anger and revenge remain our sole political horizon, we risk reproducing the same logic of elimination and punishment upon which the repressive state is built. At such a juncture, theory that emerges from within the experience of violence, rather than from a safe distance, can offer not a false pacification, but the possibility of a political pause. A pause that allows us to see how the existing order, even in moments of apparent collapse, seeks to confine our horizons of action to immediate, individualized, and death-centred reactions.

Abolitionist feminism, a feminist, life affirming form of political practice that insists that governance through punishment, intimidation, exclusion, and killing must be dismantled at its core, intervenes precisely at this point. Not to deny anger or suspend struggle, but to open a more fundamental question: is it truly possible, in the midst of catastrophe, to imagine a form of politics that insists on the possibility of life, connection, and collective liberation, rather than reproducing the logic of death? In moments of disaster, immediate responses such as information dissemination, signing statements, hashtag campaigns, and efforts to free prisoners or halt executions are necessary and vital. But we must take seriously the fact that if activism stops at this level, it ultimately remains trapped within the logic of the punitive state.

A call for a revolutionary agenda

In our present moment, precisely when everything seems to be falling apart, it is more necessary than ever to center care as a revolutionary agenda. Care not as emotional labour, but as a radical practice for collective survival and for moving forward after emerging from darkness. Radical care is not a matter of individual empathy; it is a political act aimed at survival and connection. Radical care means building networks capable of sustaining life in the absence of the state or in direct opposition to it. This form of care has many concrete dimensions: supporting the families of prisoners and those killed, recording narratives against the erasure of collective memory, and creating solidarities that break imposed isolation. In this sense, radical care becomes a form of resistance against social death.

In interviews I conducted with former political prisoners, a range of experiences emerged depending on individual circumstances. Some lost their jobs or homes after release; some saw their families fall apart; others found themselves without friends. Many require medical treatment or psychological care. All of them must attempt to reorganize their lives while grappling with post-prison and post-torture trauma. Those we call heroes are human beings walking a path on a ground marked by massacres. To understand what must be done for former prisoners we must listen and build capacities of care, not out of pity, but as part of the struggle itself.

Thinking about alternatives under these conditions does not mean designing a distant utopia. It means returning to an unfinished path and belief that takes shape alongside resistance. A belief that shifts the focus away from individual punishment and instead emphasizes transforming the conditions that make violence possible, replacing the logic of revenge with collective responsibility, repair, and the rebuilding of social bonds. In the face of a system built on physical and social elimination, the alternative offered by abolitionist feminism and care centred politics rests on recognizing the humanity of those who have been erased and reconnecting them to society.

A Politics of Life

Abolitionist feminism, intertwined with the struggle against the patriarchal logic of punishment, retribution, and killing, and with care as a vital strategy for survival, does not promise immediate salvation in today’s Iran. Yet it preserves something essential. The possibility of giving meaning to struggle and to the lives that have been lost. The possibility of refusing to submit to a current milieu that seeks to replace action with paralysis. And the possibility of a political imagination capable of taking root in collective belief. Against an order that normalizes death, this approach insists on a politics of life. A politics that resists, builds, and maintains the vision of a future without cages alive even in the heart of catastrophe.

At a moment when many potential agents of change are imprisoned, silenced, or traumatized by witnessing deaths, we must remember the necessity of radical care for ourselves and one another. This is not withdrawal or passivity, but thoughtful engagement with what we want to make possible, alongside critical reflection on our practices. At a moment when immediate and visibly effective intervention is not available to us, feminism is suppressed by the Islamic Republic and right-wing forces seeking imperialist intervention, and the death penalty is treated as normal, gathering around abolitionist feminism is difficult, but leftist feminists, considering the crisis of social reproduction and radical, collective care that envisions abolition of execution and imprisonment, can bring abolitionism to practice and respond effectively to the situation.

Solidarity Grounded in Care

We have a long history of seeking justice and of families of the killed and imprisoned coming together, including lessons from the Mothers of Justice, whose children were executed in the 1980s in Iran. These families refused to submit to the noose, and through their actions brought life back into the public sphere. By creating bonds of empathy and collective presence, they challenged the dominant narrative and transformed death and mourning into collective, life-affirming political acts.

We must look to the Mothers of Khavaran, the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, and the Saturday Mothers in Turkey and remember that we have nothing more precious to lose than what they already lost. Mourning itself can become a site of political organizing. As part of the Global South, our struggles are interlinked by shared histories of state violence and repression. Learning from one another across borders, languages, and contexts, while recognizing resonances in our experiences of loss and survival, is crucial to rebuilding networks of care and resistance.

At the same time, although it is difficult, it is possible to identify emancipatory and forward-looking narrators from among the multitude of voices and through the propaganda of dictators and colonisers, totalitarian systems, warmongers, and supporters of genocide. This act of discernment is itself part of our political responsibility. We need to return to this history and form circles of solidarity grounded in care. We must begin political organising in order to reproduce ourselves and our lives, to rise from the ashes that have been poured over us, and to shape our struggle toward reclaiming political power. The path is long, and we are tired, worn down, and abandoned. But we, the living, political activists, feminists, bear responsibility in the face of what we are witnessing. And this responsibility continues until victory.

Neda Naji is a left feminist with an abolitionist approach to prisons and the death penalty, informed by her own experience of incarceration.