Building Abolition from Scotland’s history of resistance to the prison

John Moore provides a brief reflection on last month’s event: Activating the Archives: Prisons, Abolition and Histories of Resistance organised by Martha O’Carroll and Margaret Malloch from the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research.

The event built on Martha’s research into the history of resistance to prison in Scotland in the 1970s and 1980s. Her report Is Anyone Out There? Prison Activism & Abolition in Scotland 1972-1987 is a really important contribution (as well as being a must read), which the event was seeking to build on.

The morning session started with an introduction by Martha who highlighted the range of resources she had found in her research and the importance of using this material/resources/experience of previous struggles to inform contemporary activism.

Also in the morning we heard presentations from Mike Nellis, an activist with Radical Alternatives to Prison (RAP) from 1978 to 1982, Kathryn Chadwick, a prison researcher reflecting on her research in Scottish prisoners in the 1980s and John Bowden, anti-prison organiser since his imprisonment in 1980.

Mike who had been a social worker in London became active in RAP’s work on youth justice and authored RAP’s pamphlet Intermediate Treatment and Abolition in 1979. Mike spoke about how influential RAP had been to him, highlighting a number of activists, in particular Stan Cohen. In terms of Scotland, RAP had focused on the potential of the Barlinnie Special Unit and one of their workers had visited it, interviewing Jimmy Boyle. Boyle’s book A Sense of Freedom had been influential in his own social work practice.

Kathryn was one of a number of prison researchers (others included Margaret Malloch, Phil Scraton, Paula Skidmore and Joe Sim) who had focused on Scottish prison during the 1980s. She contrasted the then official rhetoric of the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) – ‘Care’, ‘Opportunity’, ‘Responsibility’, ‘Effectiveness’ – with the reality their research uncovered of ‘harsh, brutal, over secure regimes lacking purpose and meaning leading to severe boredom, despair, frustration, anger and mental stress’. She concluded that the reality has been getting worse. There was little hope for a reformed prison and abolitionism’s identification of the failures of prison remains valid.

John was unable to attend in person and spoke via Zoom. John was imprisoned for 40 years and released on life licence three years ago. His licence conditions do not allow him to leave London. The two men convicted with John had been released 20 years ago, but John’s anti-prison organising had led to his release being repeatedly refused until he took legal action to force the parole board to stop using his organising as a reason for continuing his incarceration. John spent time in both the English and Scottish prison systems and spoke about how the solidarity between prisoners had decreased over time reflecting wider trends in class politics. Prison had politicised him and John answered questions brilliantly. In particular he intervened in a discussion of ‘what to do with the dangerous few’ by pointing out that by engaging with the question we are accepting that it is the state that gets to define who is dangerous. As prison is fundamentally an instrument of class power to maintain the current capitalist order it will be those who threaten that order who are labelled dangerous. Those who are actually the most dangerous – those with power – will remain immune.

Collectively the morning was important to highlight the long history of anti-prison struggles and abolitionist organising in Scotland. To those who claim abolition is a recent import from the United States the lesson was clear – learn your history!

After an excellent lunch we heard from four projects deploying archives for contemporary movements. Carly Guest spoke on using Islington Museum’s ‘Echoes of Holloway’ Archive, Em Elliot-Walker from Scottish Histories of Resistance, Anne O’Donnell from Oor Mad History, a community history project, and t s Beall from the group Protests & Suffragettes.

Carly spoke on the work she and Rachel Seoighe have done with Islington Museum’s ‘Echoes of Holloway’ Archive. Following the prison’s closure this project has created an archive of both women’s lived experiences of the prison and objects recovered from the building. Their work seeks to utilise these to generate an ‘abolitionist effect’ and tell Holloway’s history ‘from below’. Carly spoke of how this work supports the ongoing work to establish a Holloway Women’s building, an inclusive space deliberately located outside the criminal justice system.

The next contributor was Em who introduced the work of Scottish Histories of Resistance, particularly the project's emphasis on creating non-academic spaces. Em highlighted how the project sought to address the lack of political education within Scottish left-wing organising at a time of growing workers' resistance, the cost-of-living crisis, and a potential second independence referendum. The project was prioritises feminist and anti-colonial perspectives providing an accessible space enabling people to come together to share, discuss, research and learn about the history of resistance struggles in Scotland

Oor Mad History, a community history project recording the experiences of mental health service users in the Lothians was introduced by Anne. To date the project had compiled an oral archive of 70 activists and a physical archive of leaflets, posters, photographs and other items.

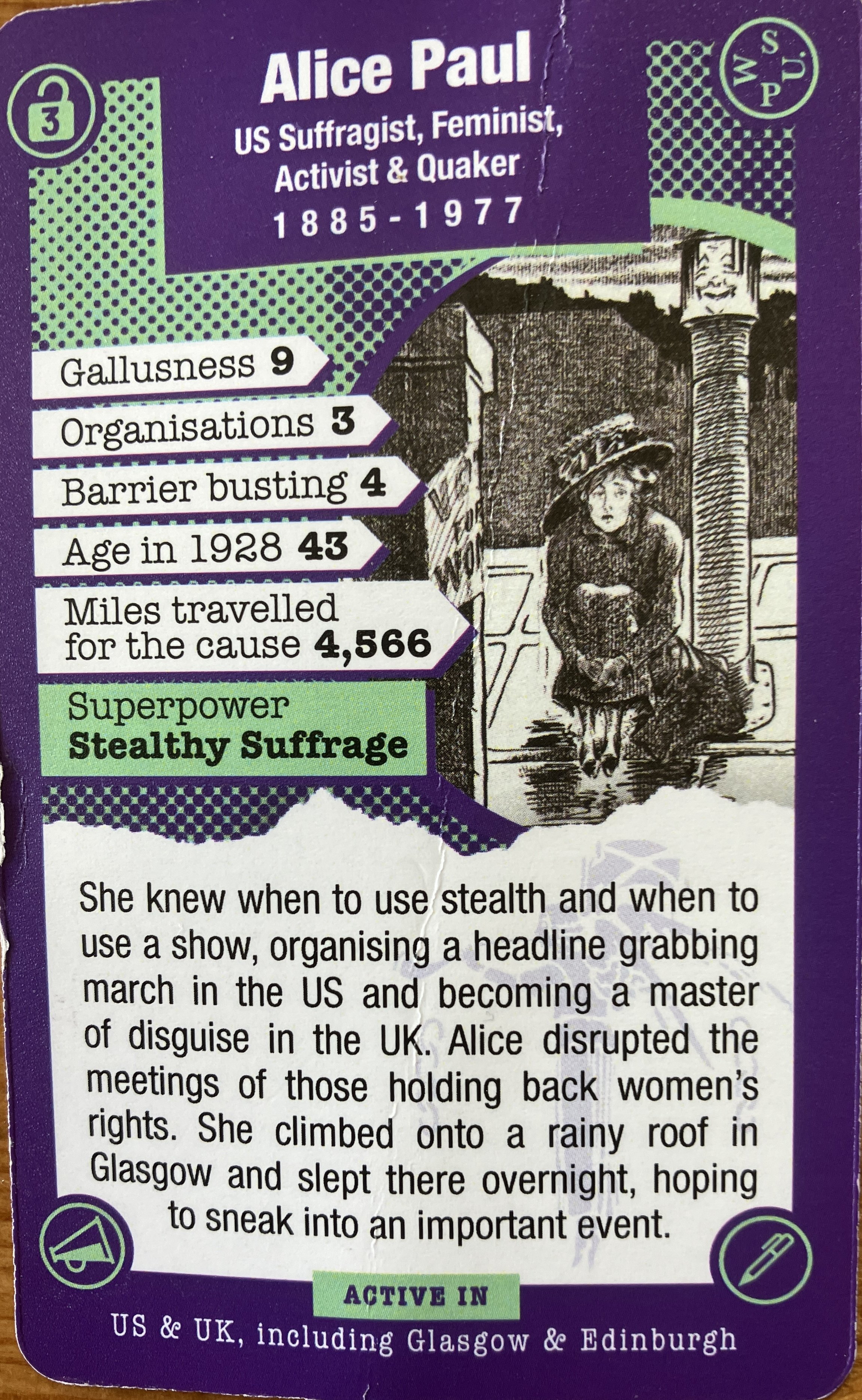

Beall, the founder of Protests & Suffragettes, spoke next on their work to recover and highlight the history of women activists in Scotland. Activists, artists and historians work collectively creating educational resources and art works as well as public walks. Beall shared stories of imprisoned Suffragettes in Scotland (yes it wasn’t just in England!) and how their imprisonment shaped the suffrage movement in Scotland. A really interesting thread of their work is activist editing of Wikipedia and the provision of training for other activists interested in this ‘knowledge activism’. There are obvious opportunities for this as an abolitionist intervention.

The event concluded with a general discussion. There was clearly a lot of love for abolitionism and a mature assessment of the potential (and pitfalls) of utilising the archive to inform our activism. The excellent abolitionist work being done in Scotland should be celebrated. My ignorance of it suggests we need to improve our networking across the island of Great Britain. Scottish comrades have offered to let Abolitionist Futures know about events and campaigns to allow us to include them in our regular ‘Abolitionist Digest’.