Remembering prison struggles from 50 years ago

By Shaïn Morisse

Fifty years ago, the summer of 1972 saw the climax of an exceptional year for British prison struggles. In total there were more than 130 collective protests, which took place in some 40 prisons. The protests involving tens of thousands of prisoners and were supported on the outside by the organisation Preservation of the Rights of Prisoners (PROP), a campaigning group set up by ex-prisoners.

The 1960s and 1970s were characterised by struggles against various institutions (schools, hospitals, factories, the army, etc.), in which material and therapeutic demands were rejected and replaced with democratic demands. These struggles were often part of the growing extra-parliamentary left and were led by people who were directly affected, marginalised and oppressed by these institutions. People who were claiming rights and offered an expertise based on their own lived experiences. In the prison arena, prisoners attempted to find a collective voice through movements that were sustained, partly thanks to external support. Drawing on my archival research, this article explores in detail the emergence of such a movement in the UK, throughout the year 1972.

Let's start by look back at the early development. In October 1969, 155 prisoners in Parkhurst prison on the Isle of Wight rioted, demonstrated and took 7 hostages. It was the largest prison revolt since the one at Dartmoor Prison in 1932, and the most violent in English penal history.

During the uprising 35 officers and 28 prisoners were injured. The causes of the revolt can be traced back to the overcrowding of prisons and the degrading conditions of detention at the end of the 1960s, as well as to the tightening of security in prisons following a series of high-profile escapes.

But the prisoners' accounts insist above all that these were a revolt against the brutality of the guards and the obstinate indulgence of their violence by the authorities, who ignored repeated complaints and efforts to raise the issue by prisoners. An example is provided by the book by Brian Stratton, who was released just before the riot.

𝑊ℎ𝑜 𝐺𝑢𝑎𝑟𝑑 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝐺𝑢𝑎𝑟𝑑𝑠? is a raw and scathing account of life in Parkhurst immediately prior to the uprising. It provides a fierce rebuttal of government and media accounts by setting out in detail the cruel and sadistic treatment inflicted by warders whose impunity lead to the revolt.

As usual, the authorities ignored the root causes of the protests and merely provided a repressive and depoliticising response. They sought to identify, punish and isolate the alleged 'ringleaders' and 'troublemakers', while simultaneously allowing the prison officers to continue to benefit from wide impunity.

The Parkhurst revolt foreshadowed the more systematic, organised and explicitly political prison movements of 1972, and the development of a radical prisoners' rights movement inside and outside prison. This movement, breaking with the elitist paternalism and uncritical line of traditional reformers (for example, the Howard League), targeted not only the conditions of incarceration but more broadly the prison’s legitimacy and its role in maintaining the (unjust) social order.

From January to May 1972, while there were about fifty collective and peaceful demonstrations across the prison estate, the prison department publicly only acknowledged a third of them and they were largely ignored by the press. In May, protests by prisoners on remand in Brixton prison (London) were the first to receive media coverage, benefiting from massive demonstrations of support by local residents. The formation of Preservation of the Rights of Prisoners (PROP) was also announced during this period.

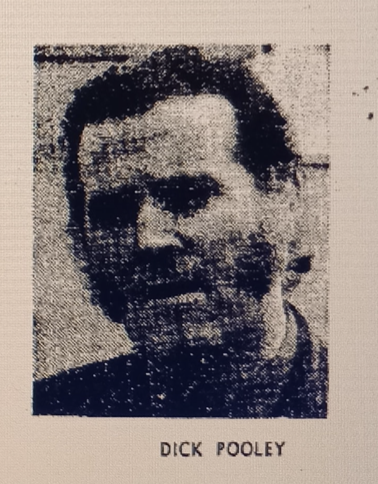

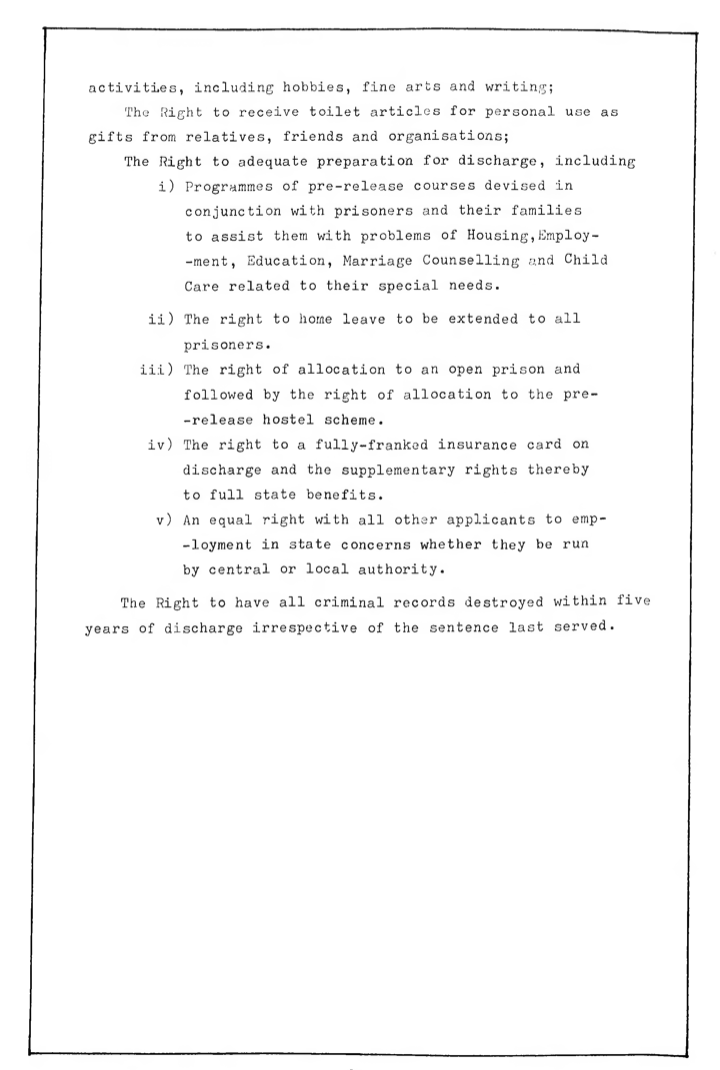

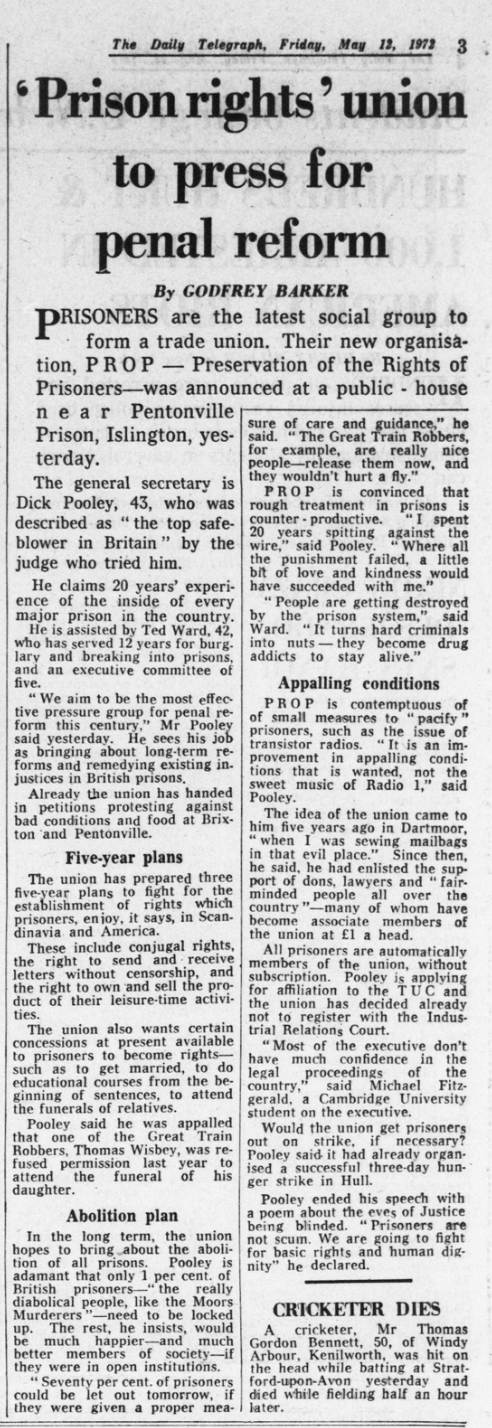

Founded by Dick Pooley, a top safeblower who spent 20 years in prison, PROP aims to challenge the authorities' monopoly on information, a monopoly used to hide the reality of imprisonment and lives of prisoners. It also sought to publicise and facilitate the coordination of inside struggles.

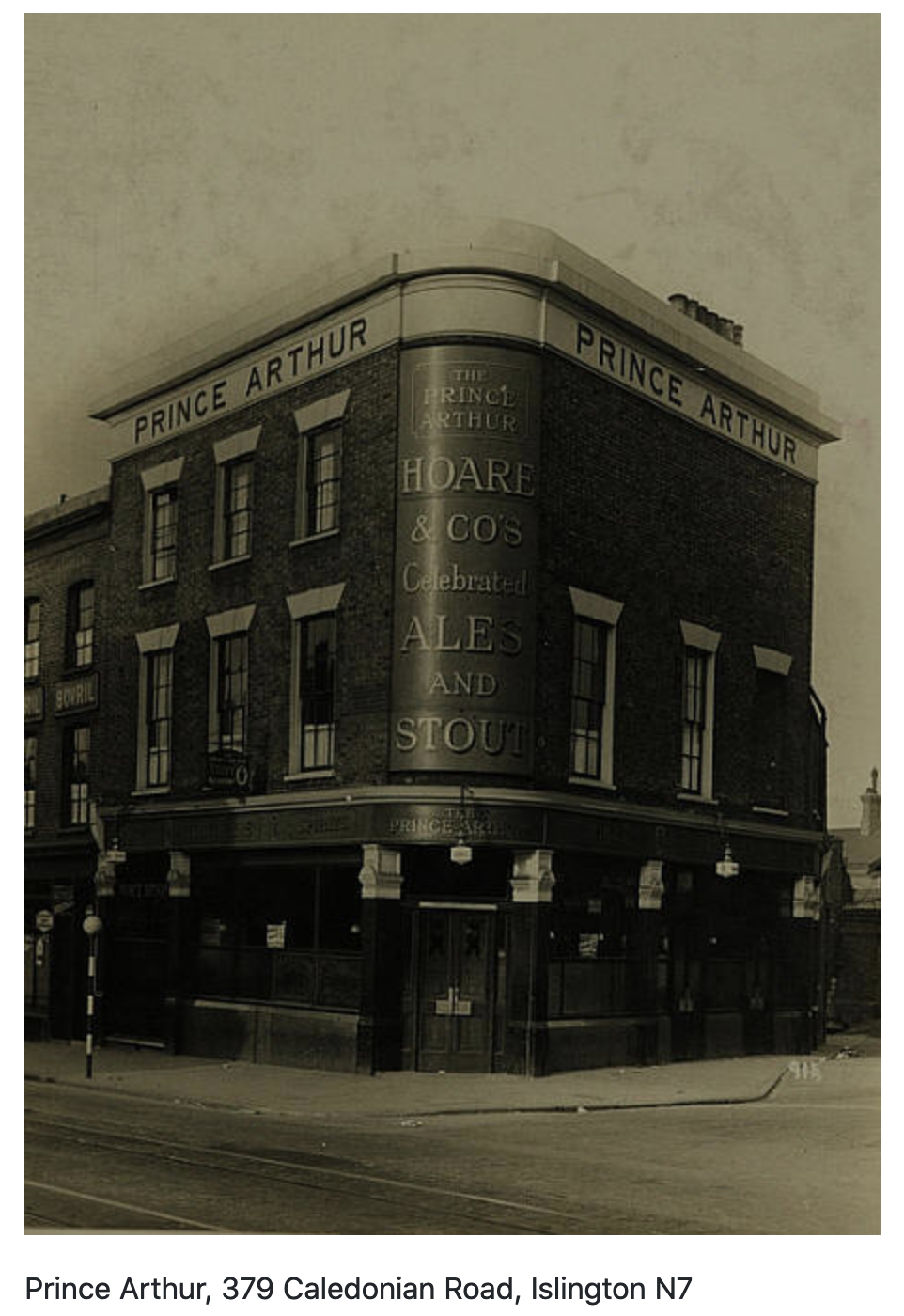

On 11 May 1972, PROP invited the national press to the Prince Arthur, a pub opposite Pentonville Prison (London), to officially launch the prisoners' union, whose demands were outlined by Pooley.

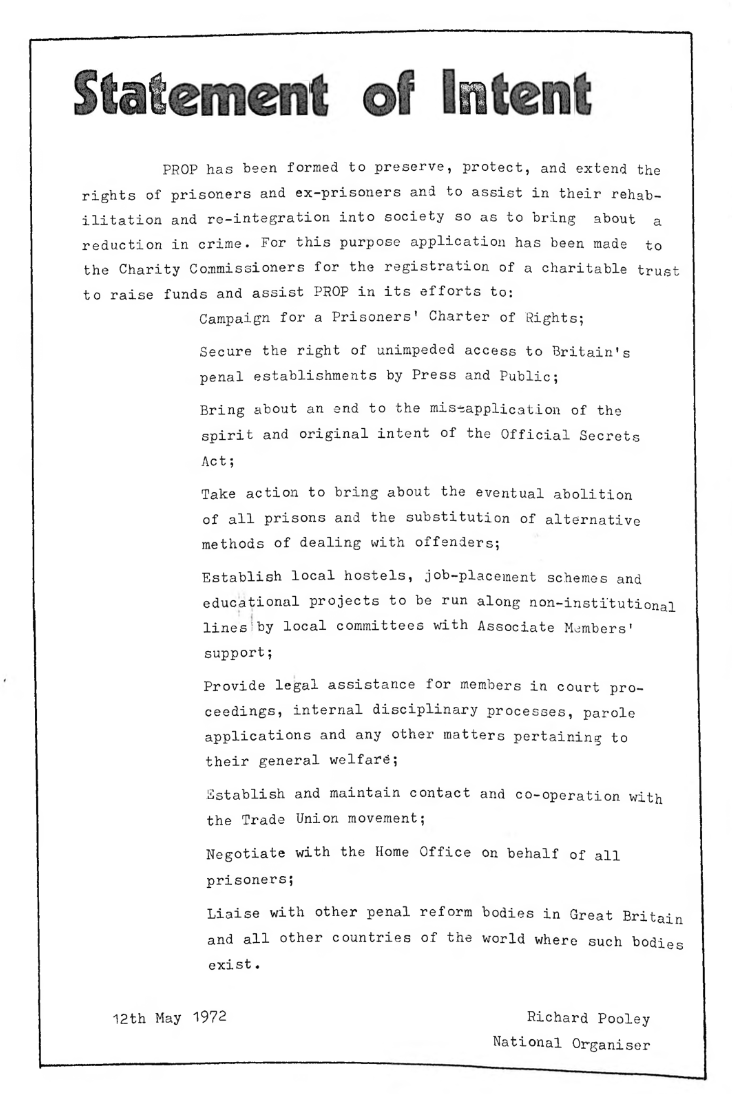

Here is the Statement of Intent, which sets out the general aims of the organisation. In addition to various rather reformist goals, there is also a wish to adopt an abolitionist perspective (but this will not be central to its history).

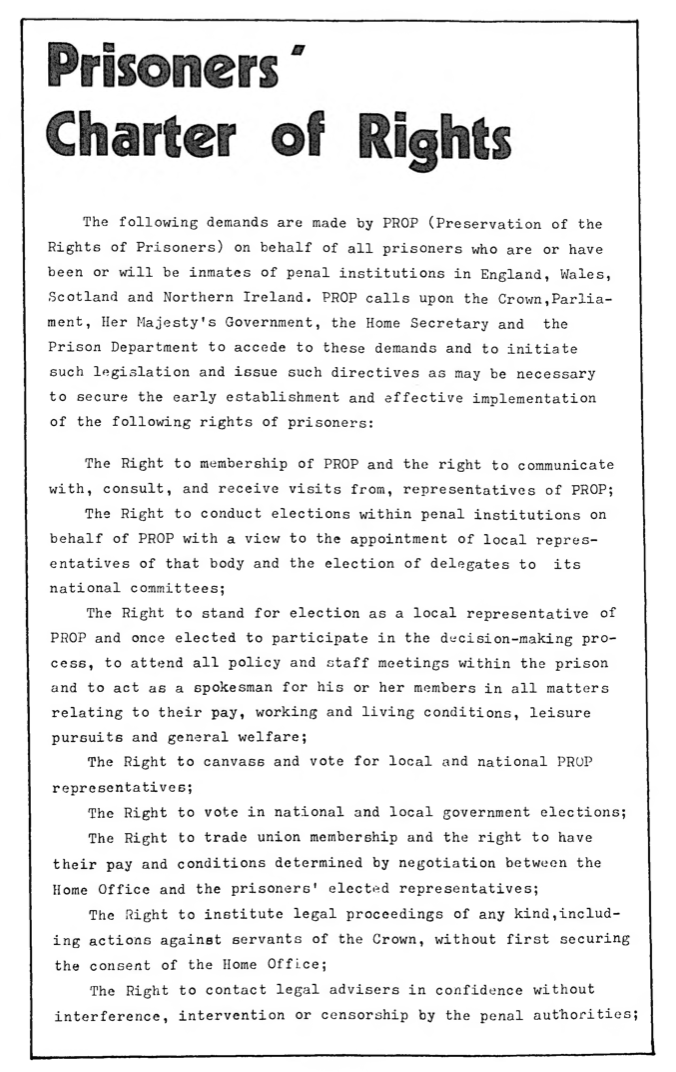

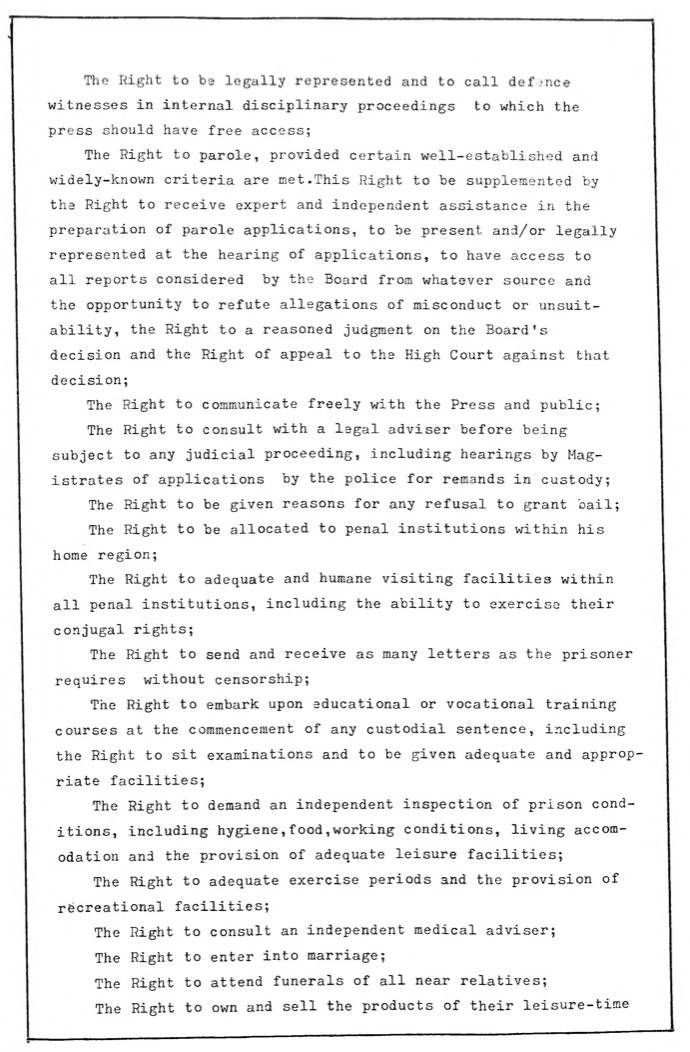

The Prisoners’ Charter of Rights lists 26 ambitious demands, ranging from political, civil and trade union rights to rights relating to the more concrete dimensions of imprisonment. The charter shows PROP's determination to act as the representative body of prisoners in dealings with the prison department, which they hoped to hold to democratic standards and accountability.

Unlike the traditional penal reform lobby, which is dominated by middle- and upper-class individuals who have not experienced prison, PROP was a prisoners' organisation that gave priority to their voice, their expertise, or, as Foucault described it, their 'subjugated knowledge'. Therefore, although sympathisers are welcome as 'associate members', only people who had been incarcerated could become full members and decide on the group's policies and strategies.

A copy of these 3 founding documents was sent to all national media and to the Home Office, thereby ensuring good media coverage for PROP, and ultimately spreading the word about the organisation in prison.

On 12 May, at PROP’s official launch in Hull, the press were not as present, but about sixty people attended and listened to ex-prisoners outlining the need for the organisation, as well as representatives from different movements who came to support the establishment of PROP. This included the secretary of the local branch of the TGWU, the largest trade unions in the country, and the Norwegian Thomas Mathiesen, who came to bring the support of the Scandinavian prison movement.

The first weeks of PROP activity were marked by the rapid growth of prison protests, a development for which the organisation claimed some responsibility. By the end of May, peaceful demonstrations had already reached more than 50 prisons and involved more than 2,500 prisoners.

Although PROP was increasingly popular among prisoners, its claim to coordinate protests was largely a bluff, aimed at giving the appearance of a large and influential group, which in turn helped its credibility and access to the media, allowing it to publicise both the protests, and what was happening in prisons in general. In practice PROP faced structurally impediments that meant it struggled both to attract outside support and to communicate inside, largely because of censorship by a prison administration that was determined to deny it any form of legitimacy.

At the end of May, given the repeated refusal of the authorities to negotiate for the establishment of prisoners' rights, PROP announced a new escalation of the protests, which would culminate in a national strike.

In early June, new sit-in strikes in more than 20 prisons received widespread media coverage and strengthened PROP’s legitimacy. Although the authorities were increasingly concerned about the growing and the organised nature of the unrest, they still refused to recognise the union. In the two months since PROP was formed, more than 45 demonstrations involving 7,000 prisoners in 18 prisons had taken place in support of the organisation's demands, and unofficial committees had been elected in eight major prisons.

As the prison demonstrations, stimulated by the transfers of the alleged 'ringleaders', continued, the threat of a strike became louder. On 20 July, PROP announced a 24-hour national strike scheduled for 4 August, with demonstrations outside prisons in solidarity. On 4 August, the first national prisoners' strike took place in Great Britain, involving between 5 and 10,000 prisoners taking part in sit-ins affecting some thirty prisons. It was then one of the largest prison strikes that have ever taken place anywhere in the world.

Over the following weekend, PROP issued the following list of prisons which supported the strike action: "Albany, Birmingham, Blunderston, Bristol, Brixton, Camp Hill, Canterbury, Chelmsford, Coldingley, Dartmoor, Durham, Gartree, Gloucester, Haverigg, Hull, Lancaster, Leeds, Leicester, Lincoln, Liverpool, Long Lartin, Maidstone, Manchester, Northeye, Nottingham, Oxford, Parkhurst, Pentonville, Preston, Stafford, Wakefield, Wandsworth, and Wormwood Scrubs.”

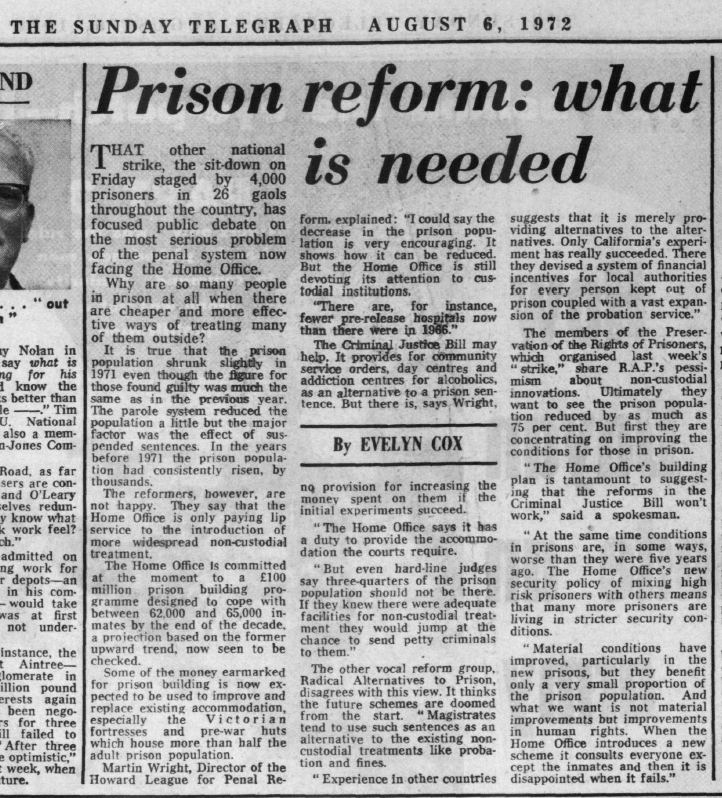

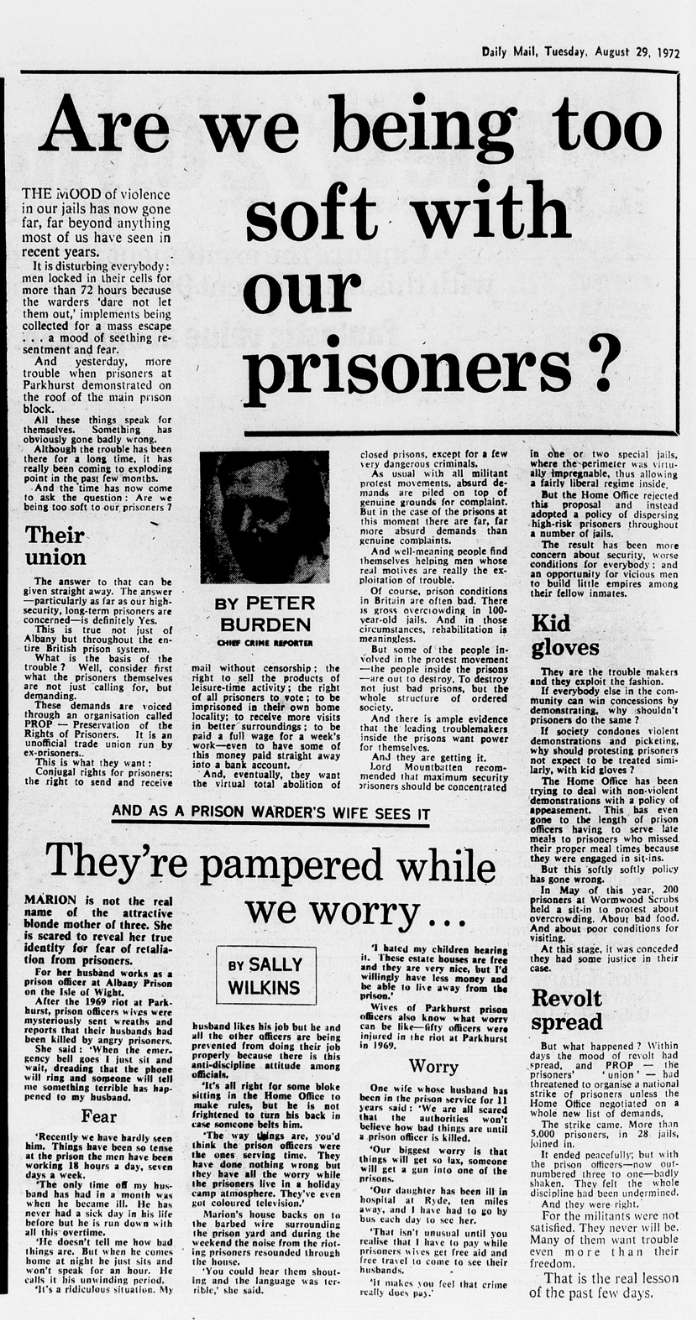

The prison strike got a lot of media coverage, often with a sensationalist or law-and-order angle. The Home Office tried to minimise the scale of the protests and their political significance, while the wardens prepared a counter-offensive and took physical revenge on the prisoners.

On 21 August, the national Prison Officers' Association (POA), the guards’ union, launched a 'get tough' campaign, calling on its members to adopt a strict interpretation of prison rules and to clamp down on and punish any deviation, even the most minor. Prison officers at Albany, on the Isle of Wight, supported by colleagues in some 50 prisons, wished to go further and publicly threatened to demonstrate in September, if tougher penalties for each breach of the rules were not introduced.

A meeting between the POA and the governor at Albany prison with its governor, immediately after which a mass escape plan was allegedly discovered. This 'revelation', which in reality concerned two men, led to a thorough search of the prison, bringing the prison’s routine to a standstill for several days. The prisoners soon realized that the lengthy search was a pretext for the wardens to retaliate for the eight massive, peaceful demonstrations that had paralysed Albany between April 1 and August 22, 1972. After an abusive search of his cell, a prisoner threw some of his belongings out of the window and tried to start a fire in the yard below. Other prisoners followed, although the fire brigade quickly secured the area.

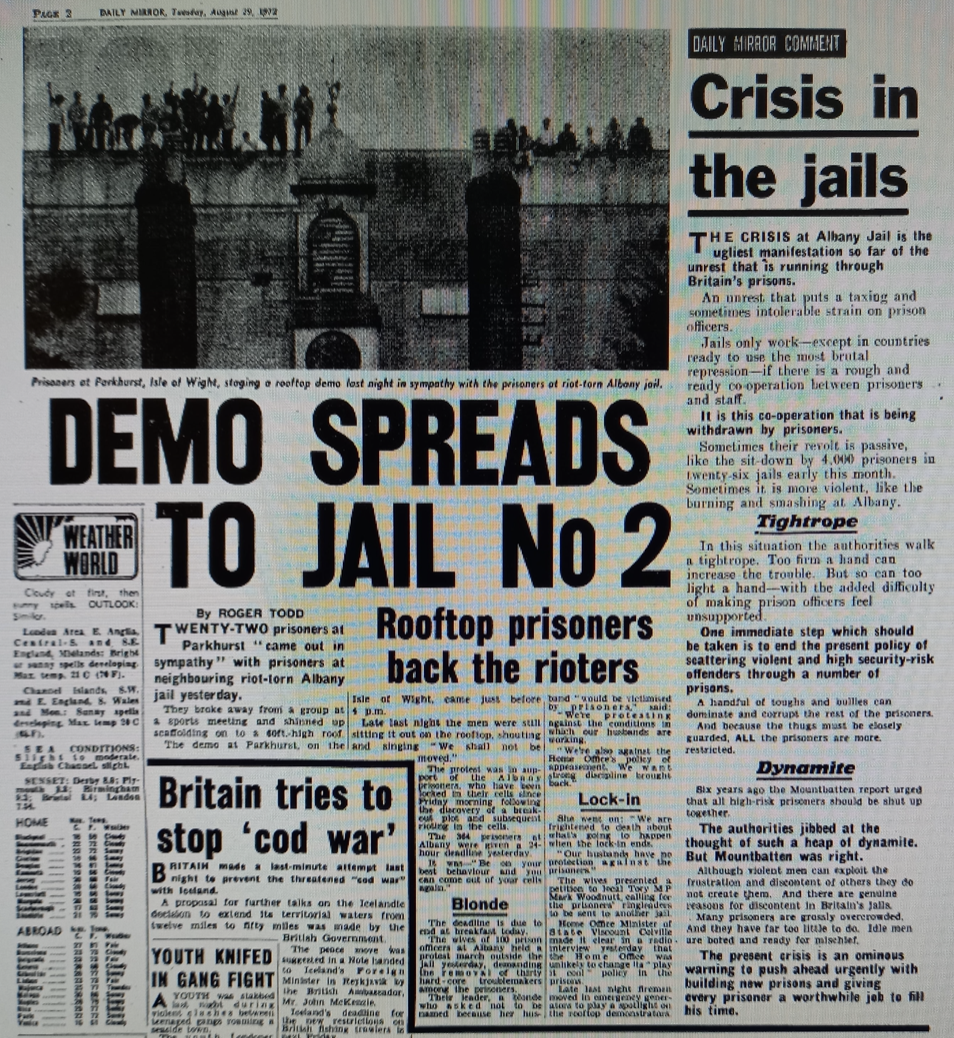

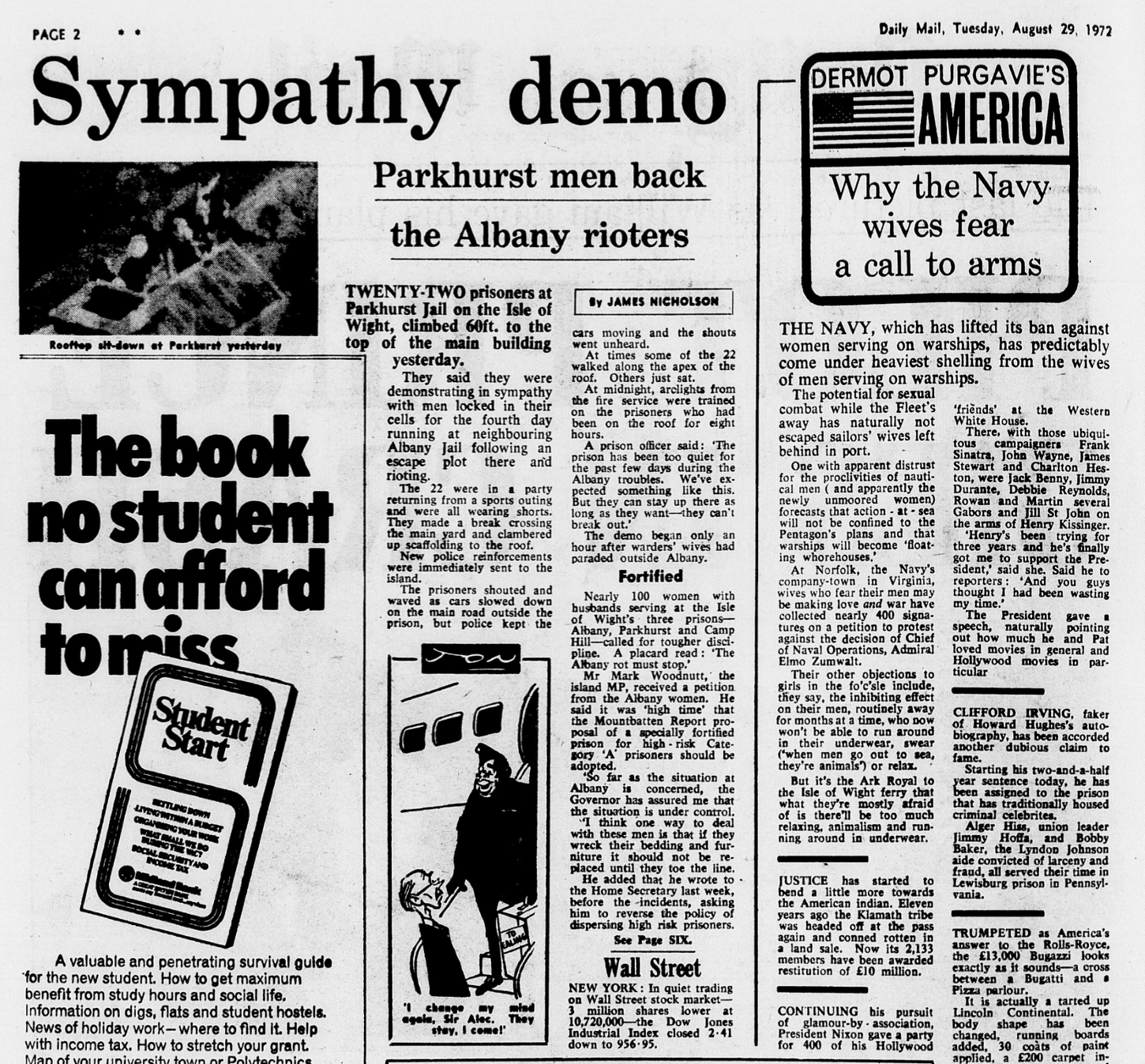

However, the next day the press echoed the officers' claims and turned the incidents, caused by warders, into a riot following the failure of an alleged mass escape plot. On 28 August, 22 prisoners from Parkhurst Prison (also located on the Isle of Wight) climbed onto the roof of their prison to support the Albany prisoners

This was followed by action at Gartree prison, where 300 men went on strike, Camp Hill and Chelmsford prisons, where 95 and 70 prisoners also climbed onto the roof of the prison, displaying a huge PROP banner.

Then the protests spread to Liverpool and Haverigg prisons, where 165 men held a sit-in strike. In Aberdeen, Scotland, 170 men hoisted a PROP banner over the roof of Peterhead prison.

As the protests expanded to various prisons (Hull, Dartmoor, Stafford, Cardiff, Oxford, Wormwood Scrubs, and others), PROP continued to bluff in the media about its influence on the protests and to urge the authorities to negotiate.

Allies in foreign organisations spread the word about the protests internationally. The pressure on the authorities grew, forcing the Home Secretary to shorten his holiday. He met with the POA, but remained steadfast in his commitment to ignore PROP.

One after another, the protests ended, with the prisoners faced fierce repression. PROP, which was in deep internal crisis, was rendered passive and powerless. In total, more than 1700 men were disciplined, some losing more than 2 years of remission.

For the rest of the year, the repression and the POA get-tough campaign increased tensions in prison. Smaller protests continued in some prisons (such as Gartree), but were suppressed by the authorities and ignored by the press.

Following an internal crisis that emerged within PROP during the intense week of the Albany uprising, the organisation struggled to overcome its organisational problems: disagreements over strategy; rivalry within its leadership; and difficulties rallying support both outside and, increasingly, inside prisons. However, PROP’s internal problems, its failure to gain official recognition and its increasing powerlessness should not obscure the unprecedented scale and nature of prisoners' movements resistance in Great Britain and in particular how their mass, self-organised demonstrations were increasingly linked to wider political objectives.

During this exceptional year, the prisoners and PROP contributed to the politicisation and mediatisation of the prison issue as never before. From then on, prisoners were able to collectively speak out to challenge the administration's hegemonic narrative about prison. This moment also broadened the critique of the institution by questioning not only its inhuman conditions, but also its very existence and, through the question of rights and unionisation, the power relations it perpetuates.

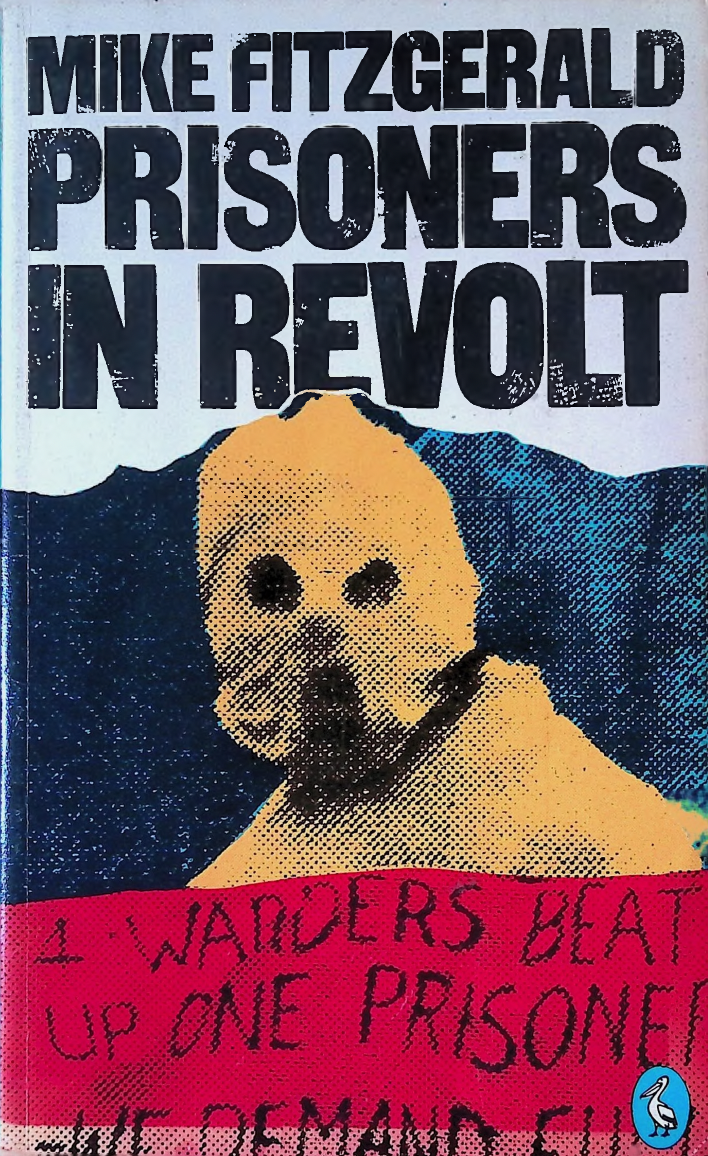

To know more about the history of PROP and the prison movement in Great Britian after 1972, please read the seminal book on the subject: 𝑃𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑜𝑛𝑒𝑟𝑠 𝑖𝑛 𝑅𝑒𝑣𝑜𝑙𝑡 (1977), written by one of its founding members: Mike Fitzgerald.

Shaïn Morisse is a PhD candidate in political science (Université Paris-Saclay / CESDIP / Centre Marc Bloch). His work focuses on the history of the movements and ideas around penal abolitionism in Europe since the 1960s. Twitter: @shainmrs