The Nancy prison revolt and the French prison movement of 1971-1972

By Shaïn Morisse

On Saturday 15 January 1972, the 300 inmates of the Charles-III prison, located in the heart of Nancy (eastern France), revolted. To celebrate the anniversary of the event, this article provides a detailed account of the protest and places this emblematic event back into the history of the French prisoners' movement of the early 1970s.

To celebrate the anniversary of the event, this article provides a detailed account of the protest and explains why it was an emblematic event in the history of the French prisoners’ movement of the early 1970s

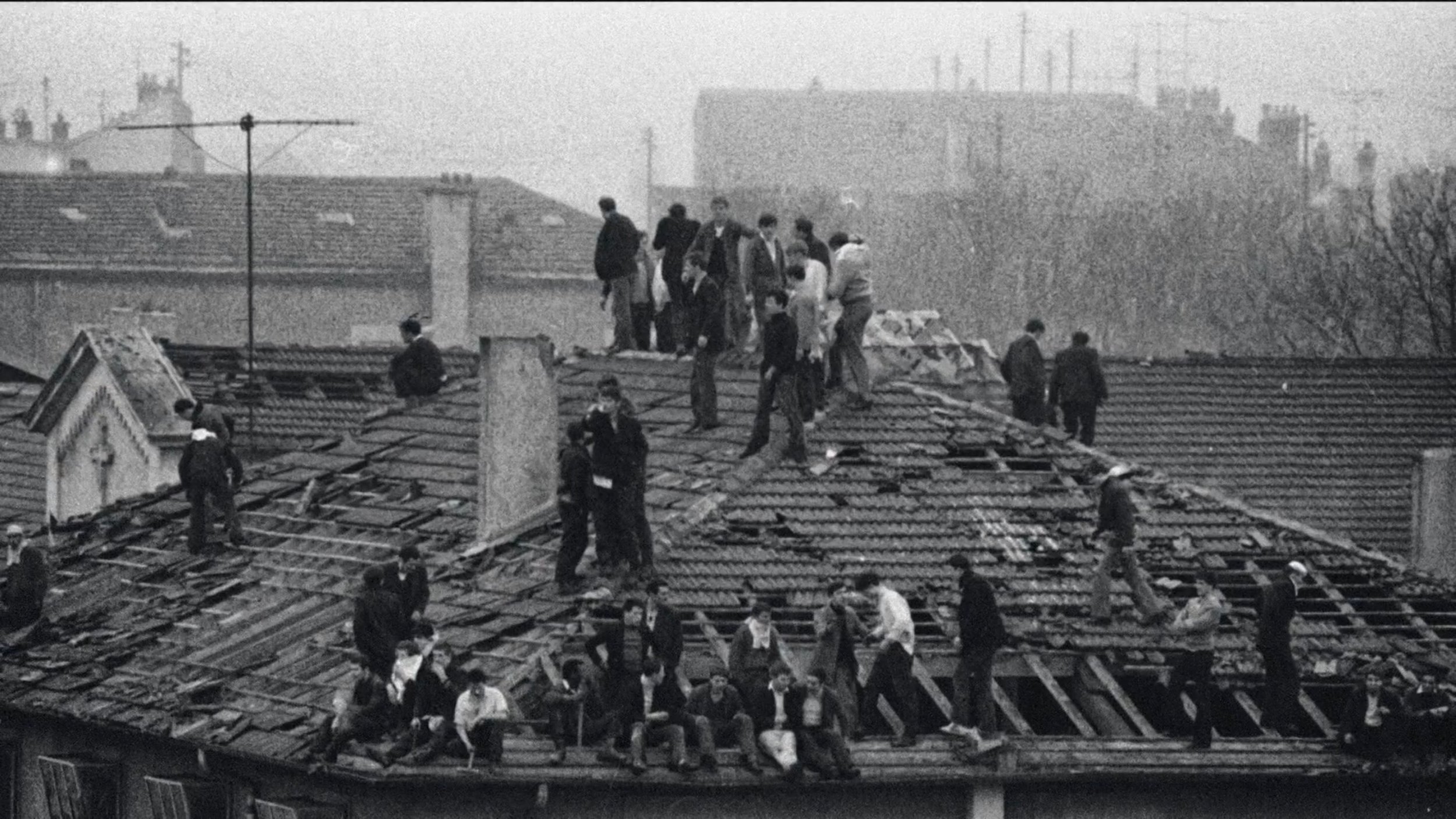

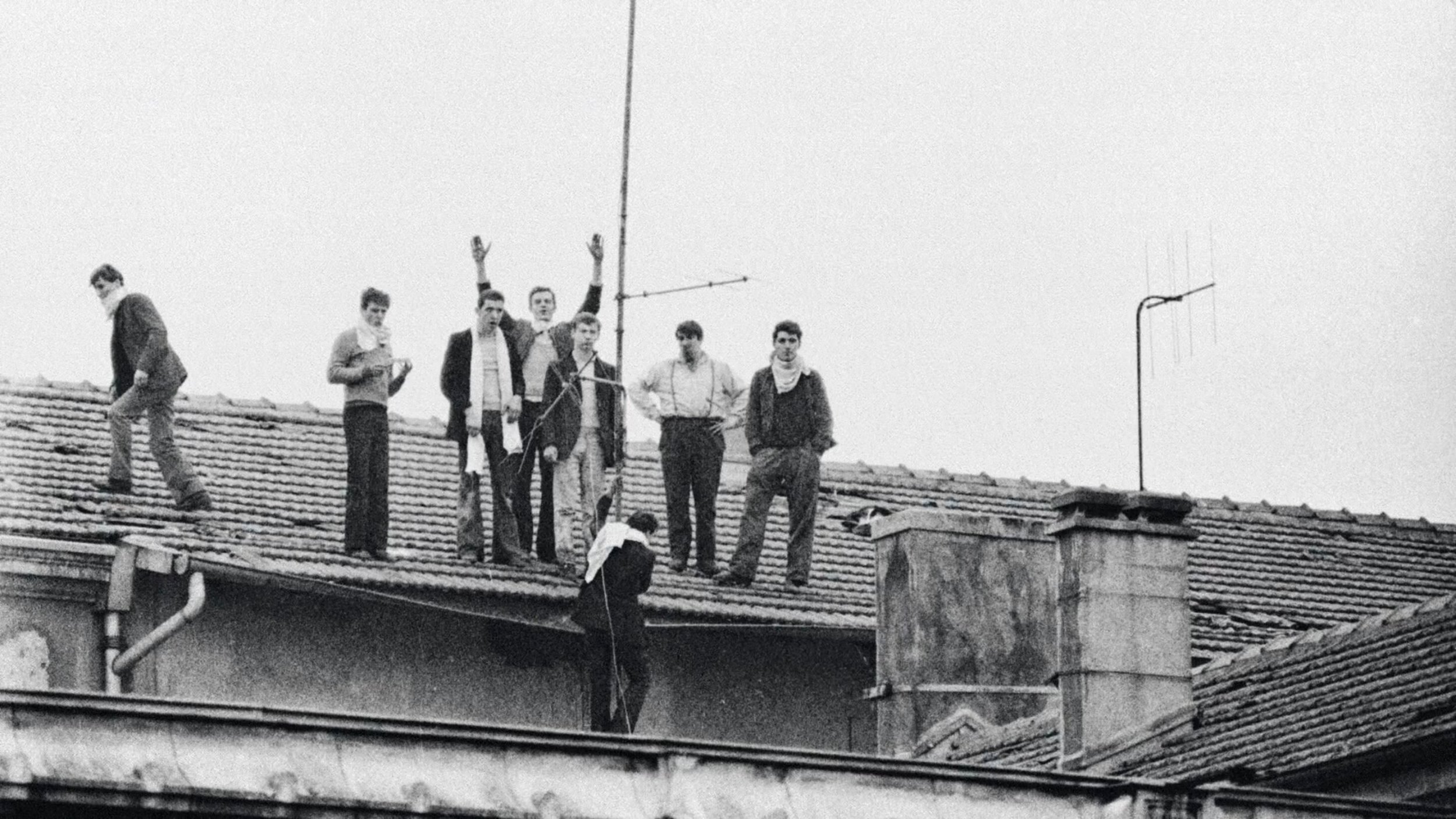

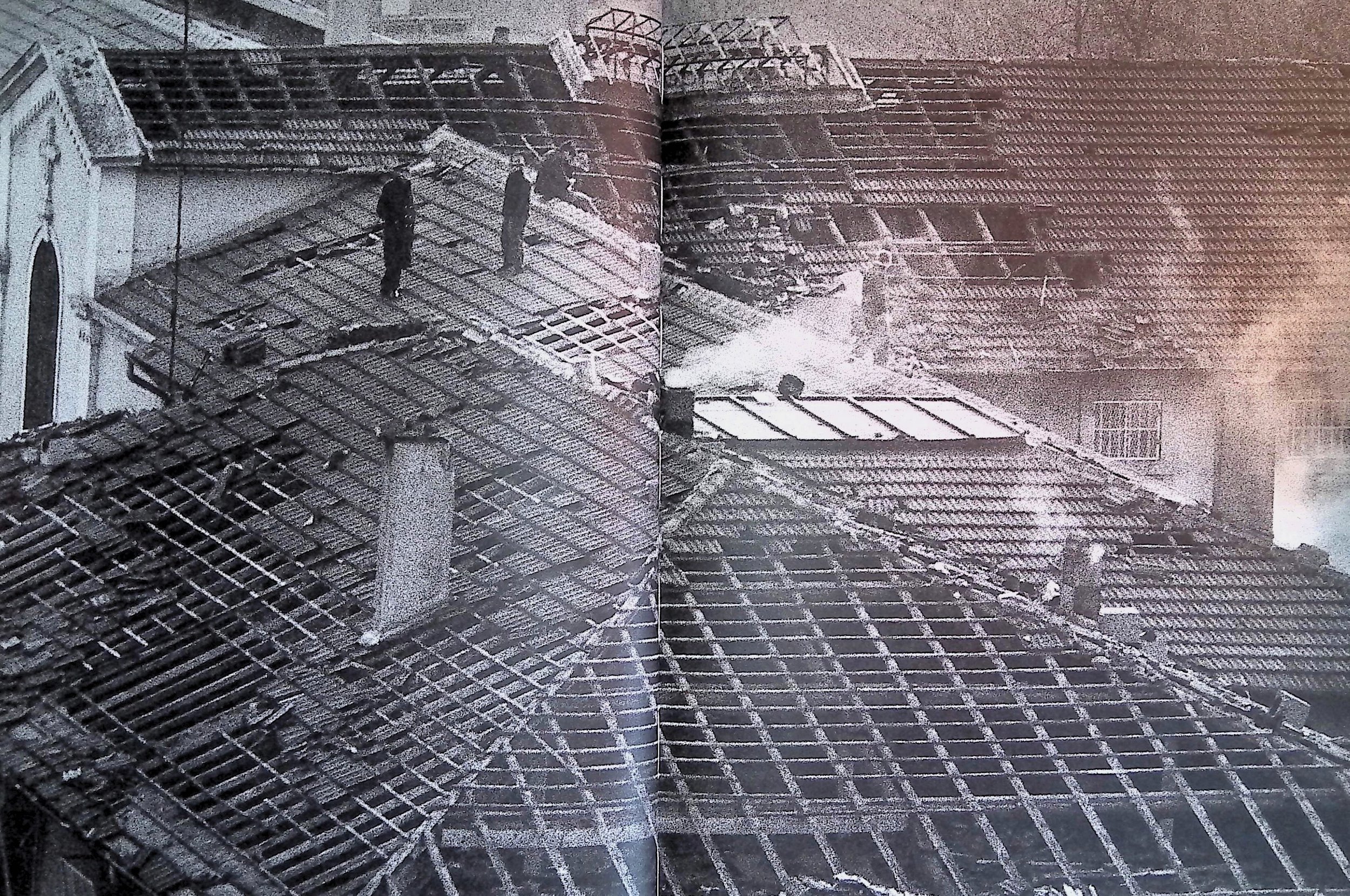

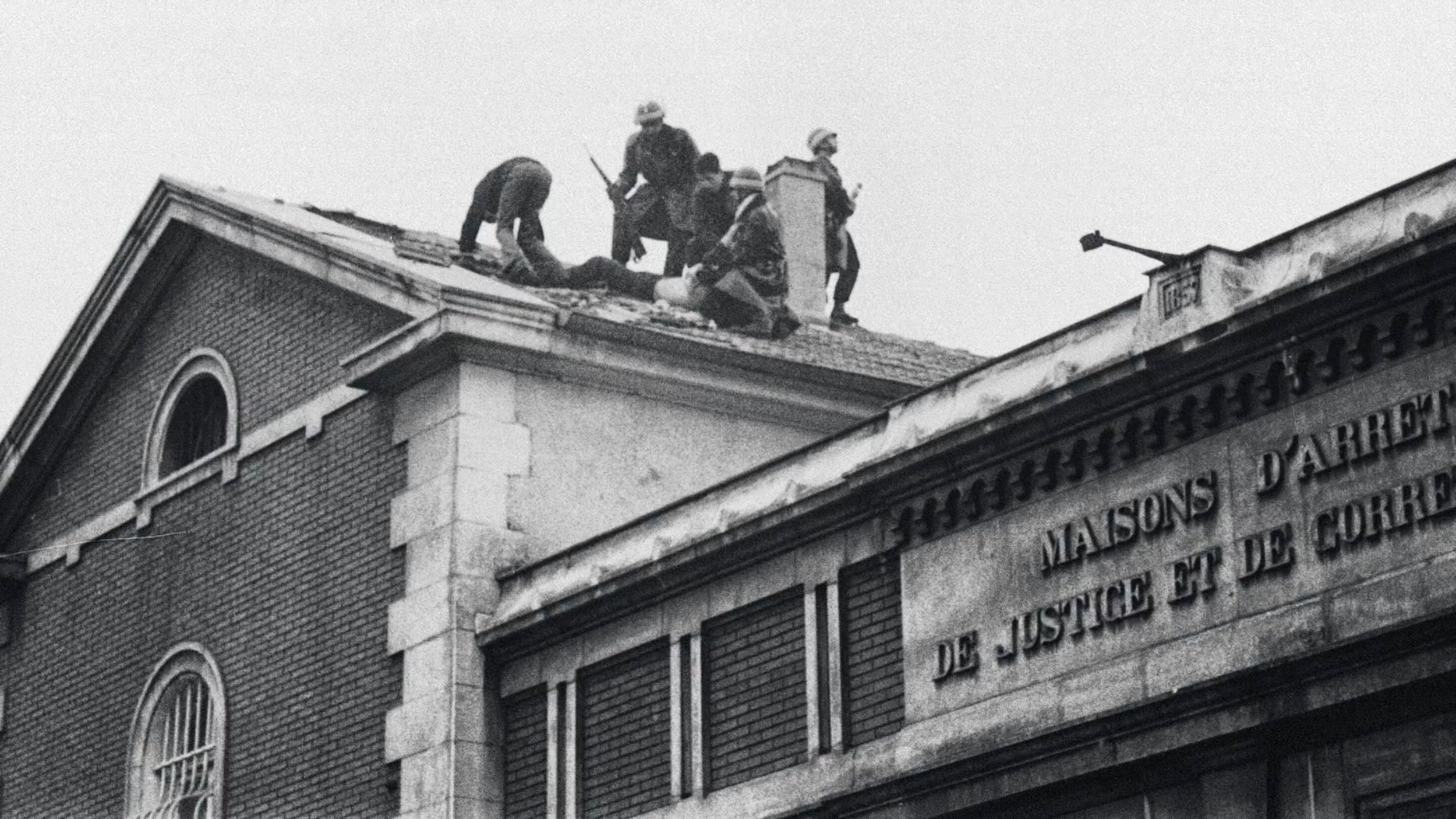

At breakfast time, an uprising broke out and spread. In less than an hour, all the inmates of the prison mutinied, took control of the buildings and moved to the roofs.

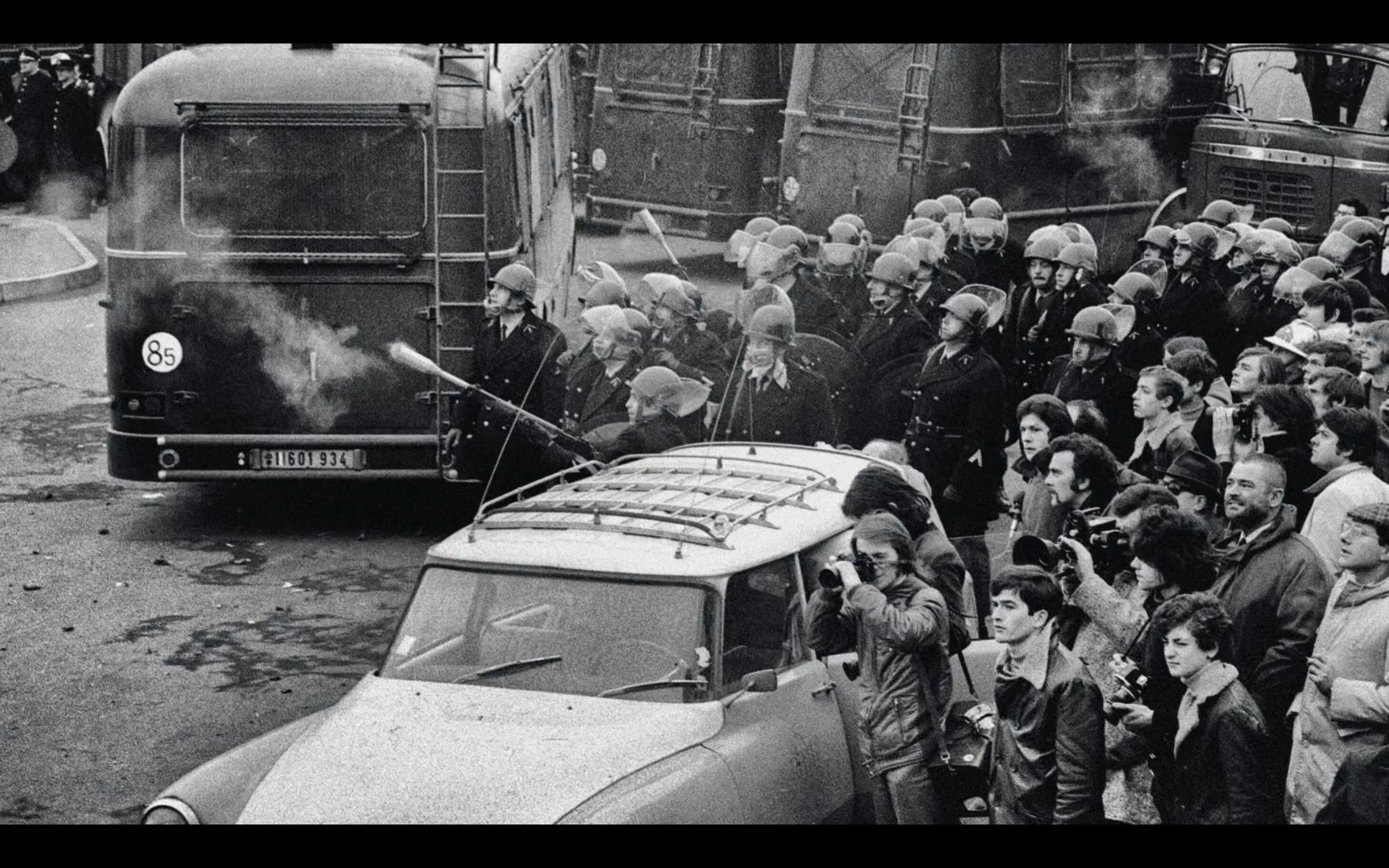

As the hours passed, the CRS (The Republican Security Corps – a paramilitary unit used for riot control) as well as a crowd of several thousand people amassed around the prison.

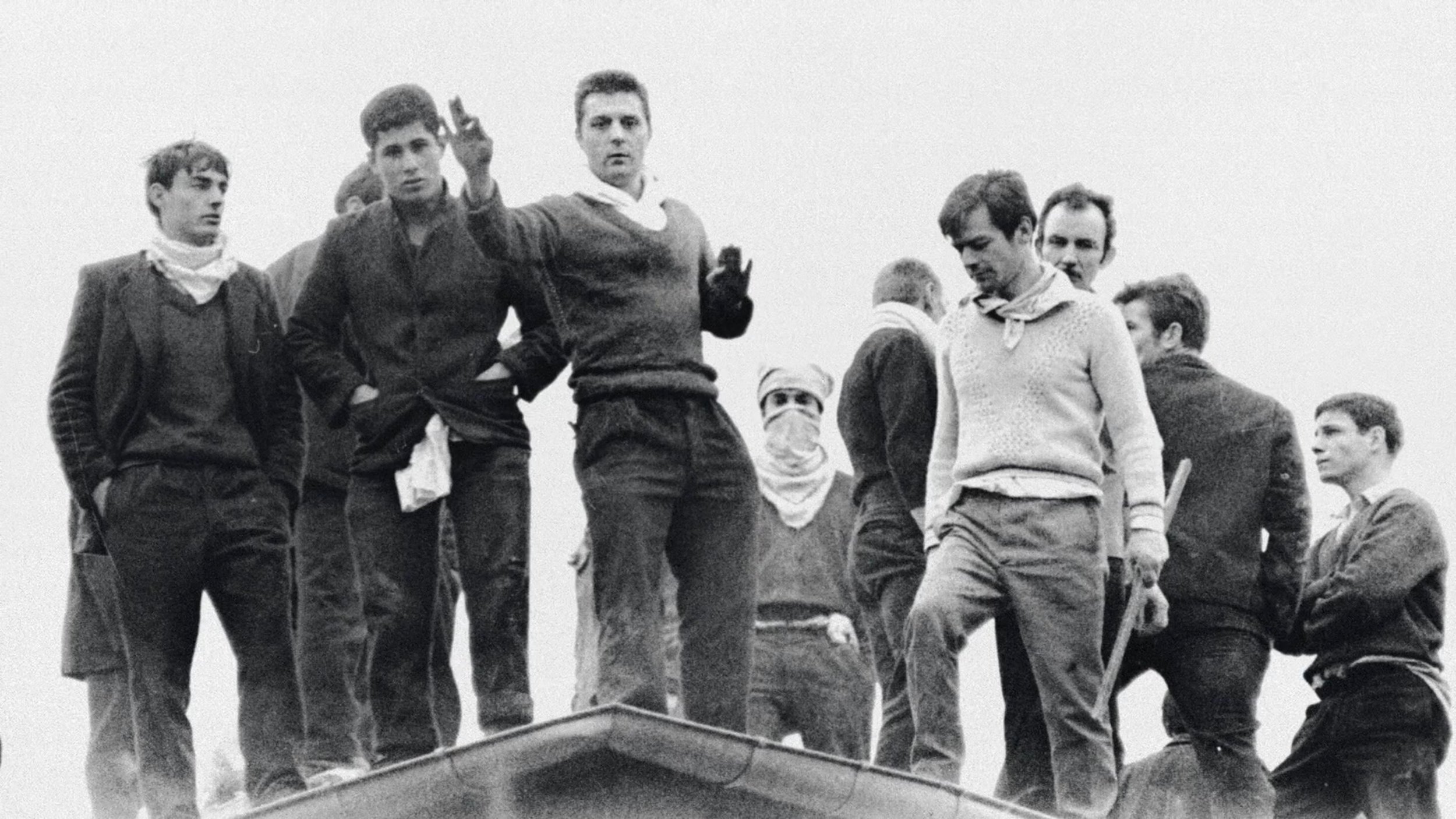

The prisoners quickly organised themselves. They intended to protest collectively and publicly against the violence and arbitrariness of the prison, against the dilapidated conditions of detention, and for rights.

Their demands were expressed with the means at hand: they printed leaflets in the administrative offices, threw out paper messages and shouted to the crowd (e.g. ‘young people, support us!’). The crowd responded and expressed its support.

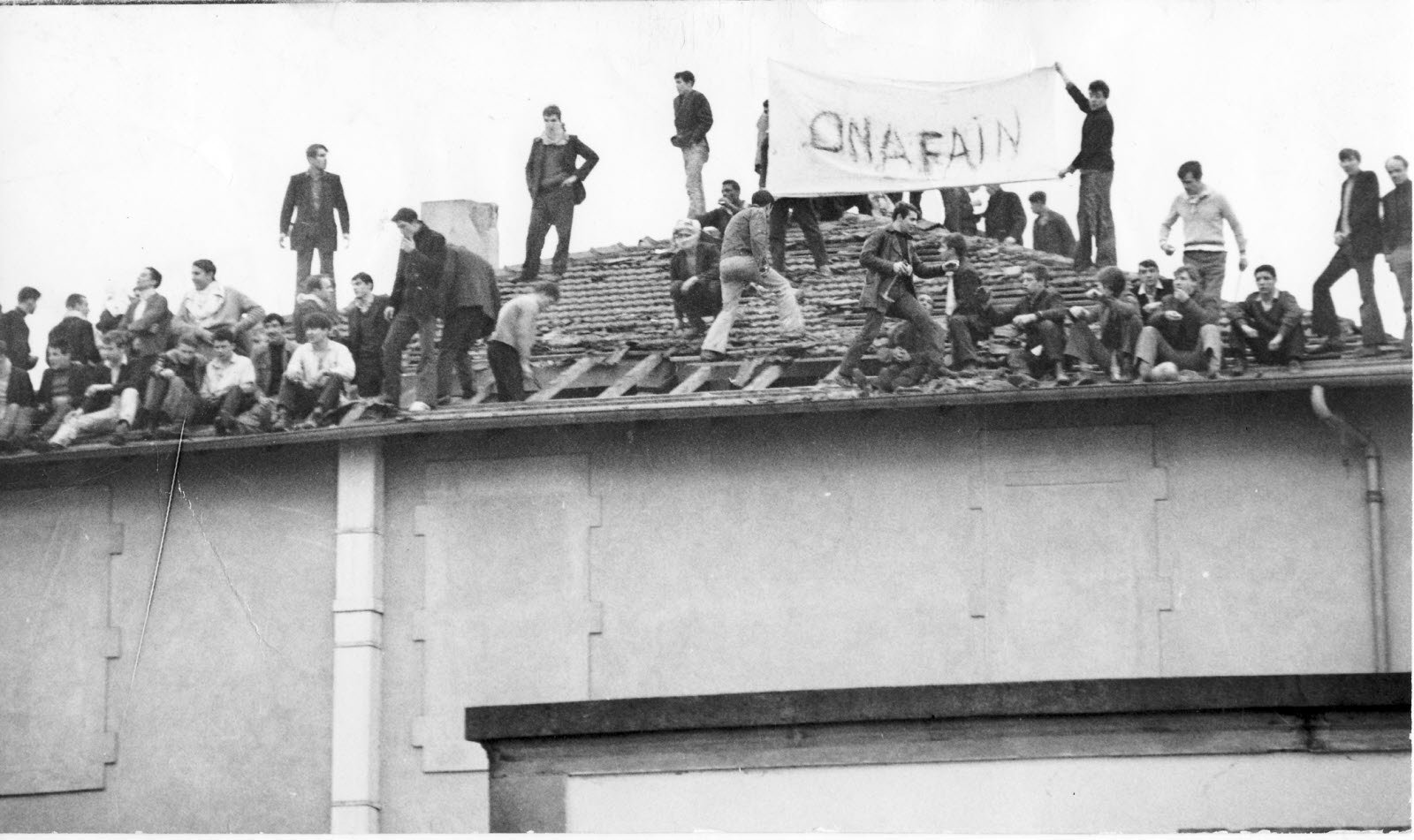

The prisoners also displayed slogans on bed sheets, which they used as banners, declaring: ‘We want prison reform’, ‘Justice’, ‘We are hungry’, ‘We are thirsty’, etc.

They also addressed a list of 8 demands to the prison authorities (translated below):

We demand fairer justice within the prison from the warders and the management.

The prisoners demand honourable justice as well as the abolition of penal supervision, the prohibition of residence

[This demand refers to a law of 17 July 1970. It officially abolished relegation for recidivists, who, since the post-war period, no longer served their sentences in the penal colony of French Guiana, but in ‘closed centres’ in metropolitan France. Relegation was then replaced in practice by tutelle pénale (penal supervision), which reproduced the same logic of stigmatising exclusion for repeat offenders who were mostly guilty of petty theft and vagrancy. Convicted offenders were thus always held in ‘closed centres’ for observation and preparation for release on parole. Tutelle pénale was only abolished when the Socialists came to power in 1981. On the history of relegation, see: Jean-Lucien Sanchez. The relegation of recidivists in French Guiana in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Christian G. de Vito, Alex Lichtenstein Global Convict Labour, Brill, pp.222-248, 2015. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01409124/document.On Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays, prisoners appearing before the Nancy correctional court are given sentences that are far more severe than those given to prisoners appearing before the court on other days. WHY !!!!!

We ask for an improvement in the everyday fare, in food.

That the canteen be improved.

We demand that newspapers are no longer censored.

We demand decent hygiene, heating in all dormitories.

We demand that prisoners no longer get beaten up by warders for trivial offences.

Prisoners of the Nancy Prison

Nancy, 15 January 1972.

But the authorities were not willing to negotiate and decided to retake control of the prison by force. To repel the assaults of the CRS and maintain the balance of power, the prisoners threw tiles at them.

At the end of the afternoon, after about 8 hours of occupying the prison, the police, supported by firefighters and a helicopter, managed to surround the prisoners and regain control of the prison, before cracking down on the protesters.

The mutiny was part of an unprecedented wave of protests against the prison regime that emerged at the beginning of 1971, when imprisoned Maoist activists went on hunger strike and the Groupe d'Informations sur les Prisons (Prison Information Group, GIP) was launched. The GIP was created by some intellectuals, including Michel Foucault, Daniel Defert, Jean-Marie Domenach, Pierre Vidal-Naquet and Gilles Deleuze, and brought together a variety of actors: legal practitioners, journalists, doctors, social workers, prisoners, ex-prisoners and their relatives. The group was driven by a common desire: to make the voice of prisoners heard, to create and disseminate knowledge about prisons and to maintain an ‘active intolerance’ against it.

‘Prison. When information is a struggle’

In December 1971, two violent revolts in a prison close to Nancy, the Ney prison in Toul, had already publicly revealed the problems of the prisons and stimulated the movement by and for the prisoners. Prison was thus already a media and political issue.

[Above Left] Front page of the supplement to La Cause du peuple (The People’s Cause), press organ of the French Maoist political party the Gauche prolétarienne (the Proletarian Left). Title: ‘Toul. The voice of the insurgents will be heard throughout France’.

[Above right] La révolte de la centrale Ney (The revolt of the Ney prison). Book on the Toul revolt published in 1973 by the Maoist ‘Comité Vérité Toul’ (Toul Truth Committee).

Although the Nancy revolt was not in itself extraordinary, it has nevertheless been a milestone, for several reasons. With massive media and photo coverage, it gave an unprecedented and direct visibility to prisoners' movements in France. But it was above all the reactions that followed that were unusual. The following weeks brought competing interpretations of the event.

The authorities tried to promote the idea of a conspiracy, a line that was followed by several newspapers, which took up the authorities discourse and highlighted the destruction caused by the prisoners’ revolt.

Article in the radical-right newspaper Minute: ‘A leftist conspiracy in prisons’.

‘The mutiny in Nancy: Heavy bill (2 million) after the ransacking of the Charles-III prison’.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, various radical left-wing groups welcomed the collective expression of the prisoners, some of them regarding it as a genuine insurrectionary moment.

‘Toul… Nimes… Nancy… When is the next one?’; Photo: GIP press conference on 17 January 1972, in front of the Ministry of Justice. Michel Foucault reads the declaration, with Jean-Paul Sartre at his side.

Supplement to the newspaper La Cause du peuple. No.16, 19 January 1972: ‘Insurgent prisoners are calling!’

From January to April 1972, these different actors carried out competing investigations into the events in order, on the one hand, to prepare for the future trial of the mutineers (six were prosecuted), and on the other hand, to put the prison on trial, through the voices of the prisoners. This was the first major trial of the prison system since the Liberation in 1945.

‘“Justice” attacks the prisoners’; ‘Nancy 18 May: Trial of six mutineers’.

“Trial of Nancy… […] … Trial of justice!”

'Those who steal bread go to prison. Those who steal millions, go to the Palais-Bourbon [meeting place of the National Assembly]'; 'Who goes to prison?

As the trial approached, the mobilisation in favour of the mutineers intensified, both inside and outside prison walls. The hearing, which for some was intended to put an end to prison unrest and for others to be the climax of the prison struggles, was finally held on 8 June.

In the end, the hearing brought the two positions face to face, but it was quickly reduced to a single day. The outcome was relatively lenient - a few months' imprisonment - but it was not the show trial some expected, or indeed, a trial of the prison as many had hoped.

Nevertheless, the Nancy revolt led to increased media coverage and politicisation of the prison issue. It has become part of the collective memory as an emblematic episode of the French prison movement of 1971-1972.

Immediately after the trial, a play entitled Le Procès de la mutinerie (The Trial of the Mutiny), based on the carefully recorded debates, was staged by Ariane Mnouchkine and the Théâtre du Soleil troupe, in collaboration with the GIP. It was performed near Paris, and featured Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Ariane Mnouchkine.

Photos by Martine Franck (Magnum Photos). The trial of the 6 mutineers of the Charles-III prison staged by the Théâtre du Soleil. Front left: Jean-Claude Penchenat and Ariane Mnouchkine as a lawyer. At the table, George Bonnaud.

Two years later, Gérard Fromanger dedicated a painting to the event using photographs projected onto the canvas: ‘In revolt at Nancy prison’ (1974).

More recently, the French historian Philippe Artières published a journal article (2001) and then a very nice archival book (2013) on the event, on which this article is largely based. Most of the photos we use of the events are from this book. They were generally taken by Gérard Drolc, Élie Kagan or Martine Frank

In 2013, Anne Guérin published a book that not only looks back at the Nancy revolt but at the whole of the prisoners' movements of the 1970s in France: Prisonniers en révolte. Quotidien carcéral, mutineries et politique pénitentiaire en France (1970-1980) [Prisoners in revolt. Daily prison life, mutinies and prison politics in France].

In 2014, Nicolas Drolc, son of the photographer who took many of the photos of the mutiny, made a wonderful documentary about Toul and Nancy, interviewing the protagonists of the time. It is available for free, in French, with English subtitles!

For the 50th aniversary of the event, the newspaper L'Est Républicain also looked back at the mutiny, with articles and numerous archive photos.

Shaïn Morisse is a PhD candidate in political science (Université Paris-Saclay / CESDIP / Centre Marc Bloch). His work focuses on the history of the movements and ideas around penal abolitionism in Europe since the 1960s. Twitter: @shainmrs