Recording & Transcript: Against Border Carcerality & Towards Abolition

Event Details

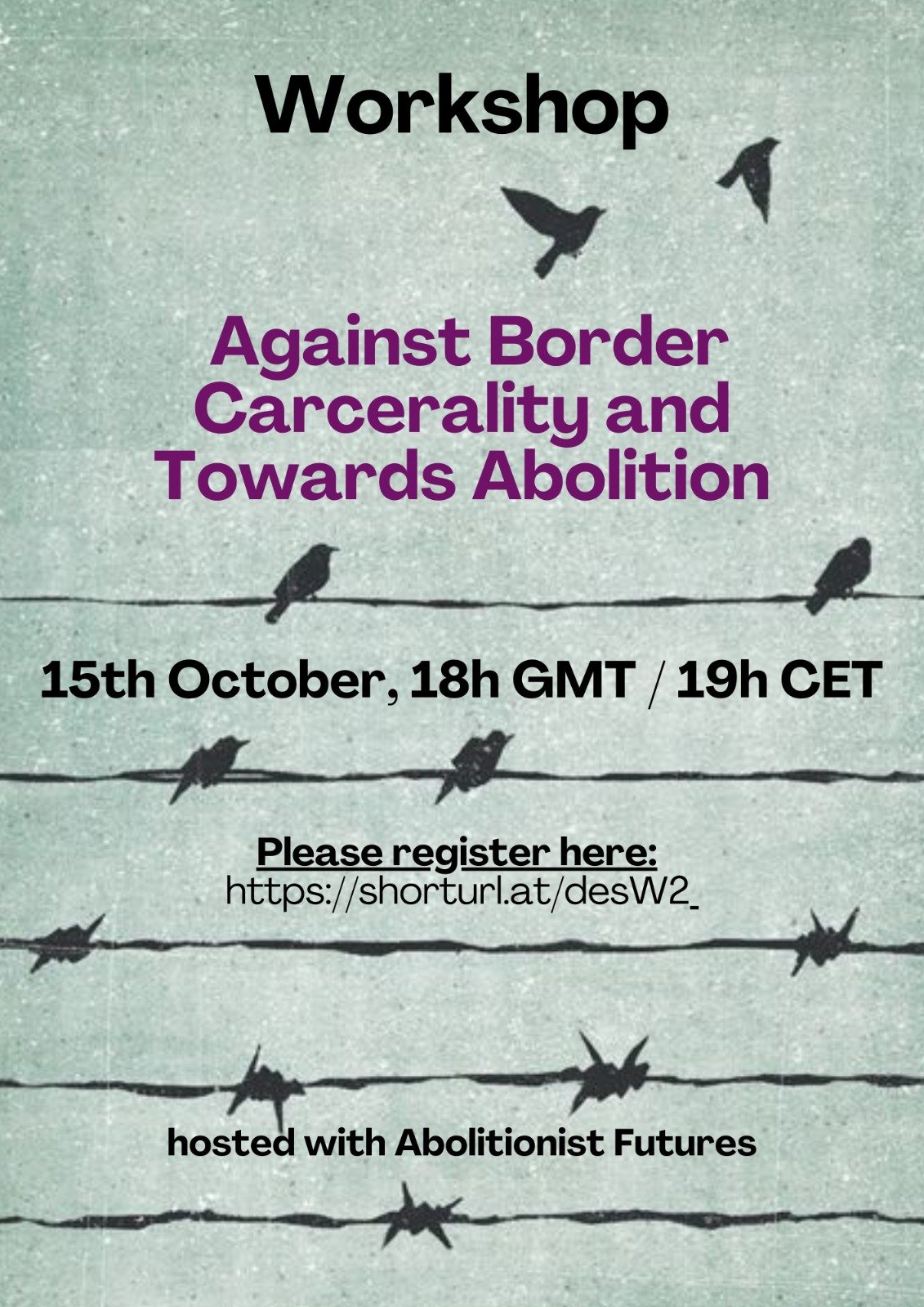

On October 15th people accross continents joined an online workshop Against Border Carcerality and towards Abolition that brought together activists, community organizers, and engaged researchers to share experiences, insights and strategies based on their ongoing struggles against border carceral systems, including detention, deportation, and encampment, across different countries and contexts.

The first part of the workshop included interventions by five speakers, who reflected on the urgency of abolitionist approaches in a time of expanding border carceral structures:

- Setareh, Detention Watch Network, USA

- Cheikh & Madieye, Ragazzi Baye Fall / Maldusa, Italy

- Gee, Association of Visitors to Immigration Detainees (AVID; UK)

- Steve, Silent University, Germany

You can watch the video recording or read the transcript below.

The workshop marked the beginning of a conversation around border carcerality and abolitionist struggles around the world. If you are interested in learning more and wish to join any future event, do get in touch!

Video

Transcript

FRANCESCA: Please, start. So, hi everyone. My name is Francesca and together with my friends and comrades, Annika and Teresa, we have been organizing this workshop with incredible support of Abolitionist Futures, especially Mo and Lorena, whom we would like to thank for their valuable assistance and insights throughout the process. Also, a big thank to all our interpreters who will allow us to share experiences and struggles across borders and across languages: Luke, Marcella, Elena, and Laia. Thank you very much.

The aim of this workshop is primarily that of offering a space to connect groups and activists who work in different local and national contexts, who struggle against border carceral violence in the form of detention, prison, and deportation camps. At this moment, we are witnessing an expansion of violent systems to control and criminalize people on the move. The right to asylum is being dismantled and violent border enforcement is increasingly externalized through neocolonial agreements, such as the one between the Italian and Albanian governments. While we are talking, the first 16 people are being violently taken to Albania on the Italian military navy, Libra. At this critical juncture, we believe it is essential to connect our struggles, to challenge this oppressive system and strengthen our resistance. We also believe that in doing so, the vocabulary of abolition can inspire us to advance our struggles. To us, abolition is a term that well captures our aims of dismantling the violence that people on the move and racialized as migrants face, not just through detention and carceral sites, but through the multiple layers of racist policies put in place by state and corporate private actors. As Ruthie Gilmore says, abolition is a method rather than solely a name, a method which allows us to dismantle, even if bit by bit, these violent regimes. However, abolition is not just about dismantling, closing down violent carceral sites, letting people out, but it's also about building. Building the collective conditions to render borders, prisons, detention, obsolete. In other words, building the world we want to live in, where there are no violent borders and divisions and where we can all flourish together. This means, as Ruthie says, basically changing everything. So this workshop is in the space to discuss what abolition and its underpinning world-making project means to us and how it translates into our local struggles and contexts; whether or not the vocabulary of abolition is useful to build our collective power across borders and if tensions exist between our efforts to abolish the carceral border systems and the need to respond to the immediate need and survival of those affected by that.

Please be mindful that this is a collective space where we want everyone to feel comfortable sharing and learning from one another. This means that we can all make mistakes and we can address them as they come up. It also means being collectively attentive to our positionality and the space we take when we speak, particularly when we benefit from structural conditions of privilege. It is important to listen to our comrades, particularly when they speak from positions of structural and systemic oppression and have lived experience of the forms of violence we seek to dismantle.

The workshop will be structured into three main parts. We have planned the first part with some intervention that will inspire our conversations tonight. In the second part, we'll break into smaller groups for discussions where we can share experiences, visions and build on the insights from earlier. Finally, in the third part, we will come back together to share key points and some concluding thoughts. In between these parts, we'll have short breaks with energizing music. Also, please note that this first part of the seminar will be recorded and will be then posted on the Abolitionist Futures website after the event. The rest of the session and the breakout room work will not be recorded. So no participants will appear in any parts of the recording.

So this being said, let's move to introducing our speakers tonight. So the first speaker is Setareh. Setareh is the advocacy director at Detention Watch Network, where she works alongside other staff and members to abolish immigration detention in the United States. Setareh immigrated in the United States as a toddler and has been involved in social justice movements for over 20 years. Thank you very much, Setareh, for being with us and sharing your experiences and struggles. Yeah, the floor is yours.

SETAREH: Okay, hi everyone. I'm just going to share my screen quickly. Can everyone see? Yes. Okay, great. So I'm going to talk a little bit today about what abolition means to Detention Watch Network and how we sort of put the theory of abolition into practice. So just, excuse me, first a little bit of background on Detention Watch Network. DWN is a national coalition building power through collective advocacy, grassroots organizing, and strategic communications to abolish immigration detention in the United States. We have over 100 organizational members across the country, across the United States, ranging from local grassroots organizations to national NGOs, and we also have individual members who have experienced detention, and we facilitate a leadership and organizing program for people who have experienced immigration detention. Our ultimate vision is a world where every person is able to live and move freely and where racial equity is the norm and where migration is not criminalized. We recognize that our work is part of a broader movement against racism, against xenophobia, and against incarceration, among many other things. We believe that in order to achieve the end of immigration detention, we need to shift the paradigm around immigration policy from one that centers punishment and deterrence and keeping people out to one that promotes dignity and freedom. And we practice abolitionist theory in the way that we go about achieving our vision, and I will talk a little bit more about how exactly we do that. Actually, I just want to make a quick time check just so I don't go over time. I might not get through everything, but we'll have a chance to talk more in the breakout rooms if I don't.

So first, I want to say before talking more about the theory, there's a few things that we kind of recognize as sort of a starting point. We recognize that the struggle to end detention is not going to be won overnight. It's going to take time. There's going to be reforms along the way and steps, and the question for us is how do we evaluate those steps and how do we know that the changes that we're making are actually taking us towards abolition? We also recognize that detention is just one part of the broader enforcement and deportation system and that detention really exists to serve that purpose of border enforcement and deportation. And then, you know, obviously I would be remiss not to recognize that the work of our allies in the criminal legal space is critical to how we think about abolition in the immigration context. And so we really look to that movement, the movement against mass incarceration and prison abolition for, you know, inspiration and guidance.

So what is an abolitionist reform and what is a reformist reform? So when we're thinking about our work, our advocacy, and our organizing and how, you know, what are the policies that we support? What are the types of changes that we're pushing our government to make? Are they abolitionist in nature or are they reformist? So what do we mean when we say those words? When we say something is abolitionist, we really see it as something that is taking us, moving us closer to abolition by chipping away at the system. And it's doing that without expanding the reach of the system or creating new harms. Because a lot of times some of the policy changes that have, you know, been sought, they may improve one piece of the broader system, but actually it's sort of strengthening the system as a whole. And so that's what we call reformist. Those are interventions or changes in policy that may on its surface seem like a progress, but in fact maintains or expands the infrastructure and reach of the enforcement and detention system.

So when we were thinking about you know, how do we determine if something is abolitionist or reformist? We again, as I said before, look to the example of our allies and comrades in the criminal punishment space. Look to the resources that they have provided us and sort of adapted some of those resources for our own uses. And we came up with a series of questions that we ask when we're considering a policy. You know, are we going to endorse a specific piece of legislation or are we going to push for different changes in the system? So the first question we ask ourselves is does this policy or this change reduce the scale of detention and surveillance? Does it actually make it smaller? Does it put fewer people in the system? Two, does it chip away at the current system while not creating any new harms or without helping some people at the expense of others? A lot of times we'll see that proposals will sort of elevate one particular group of people as deserving while at the same time kind of targeting another group as undeserving. And that's something that we don't want to replicate and we don't want to do. So are we chipping away at the system without doing it at the expense of some other group? And then three, are we actually making a difference in the lives of people who are right now detained or under surveillance, or who could be, who are in immediate harm or at risk of being in detention? So those are, and you know, we actually use these questions all the time. I mean, this is something that comes up in our work regularly as we work with partners, you know, we're working on legislation, we are working on pushing policy changes within the administration, the executive branch of the government. And whenever something new comes up or whenever we're kind of deciding, is this something we want to work on? These are questions that we are constantly asking ourselves. And we created a resource that it'll be linked at the end of my slides and I can drop it in the chat later, to provide some examples of like, okay, so we have these questions, what does that mean in actuality? So I will go through a couple of examples and then you know, happy to sort of answer questions or talk more in the breakout rooms.

So at Detention Watch Network, one of our main campaigns is the Communities Not Cages campaign, where we work really closely with local grassroots organizations who are actively trying to shut down detention centers in their communities. So this is obviously, we have decided that this is an abolitionist step. And so why is that? If we're able to close or shut down a detention center, we're immediately able to reduce the scale of detention. We have taken offline some capacity for the system. It doesn't create new harm because it's literally taking away. And it provides an opportunity for people who are in that facility today, who are in detention to be released because closures oftentimes, you know, create the space for us to mount defense campaigns to get people out of detention and to stop their deportations. So we recognize this as an abolitionist step, but we also recognize that sometimes there are tensions within that. So we really do need to work on pushing for releases. And I'm going to stop there since my time is up. And I look forward to getting into some of the questions around what are the tensions that exist in different interventions, whether they're abolitionists or reformists in our breakout rooms. So thank you.

FRANCESCA: Thank you so much, Setareh. That was really inspiring and really important to also guide us in our struggles that are often complex and involve also different temporalities. So our next speakers are Cheikh and Madiyeh. So Madiyeh is part of the Ragazzi Baye Fall Crew. He is the vice president of the Maldusa Association in Lampedusa and Palermo. And Cheikh is vice president of the Ragazzi Baye Fall Crew and coordinator of the Maldusa Palermo Station. So together they run projects in solidarity with criminalized migrants and in particular boat drivers, captains, who are currently in prison or on trial. They do so by organizing letter writings and also organizing legal and material support to those imprisoned. Thank you very much for being with us, Cheikh and Madiyeh. The floor is yours.

CHEIKH AND MADIEYE: Okay, ciao a tutti. Good evening, everyone. I'm Madieyeh. I belong to Ragazzi Baye Fall in Italy. Can you hear me well?

FRANCESCA: Yes, we can also see you, apart from hearing you. Maybe you could get closer to the microphone?

MADIEYE: As I was saying, what do we mean when we say abolitionism? In my opinion, detention centers should not exist. Detention camps should not exist. Just like jails. So it is important to know what these centers are like. It is super important to know what they are like. In our association, our main target is trying to support our brothers and sisters who are incarcerated. We know how difficult it is for them to live within these centers. And since we are foreigners, we have thought that it was important for us to give them our support. It's our duty as brothers and sisters. So we have the same mission as abolitionists. We are going to try to improve in our support activities. This is our duty.

CHEIKH: Hi, everyone. I'm Cheikh Sene. I belong to the association Ragazzi Baye Fall and the association Maldusa. We are African young people who have lived within the Italian jails. The experience was awful. And we think it is our duty to be activists. It is our human duty. And the fight is really hard, very difficult. Many of our brothers and sisters are incarcerated. After a very long journey at sea, they have lost everything. They have lost everything. They have lost their country of origin, and they are in a very difficult situation. So once they get to Italy, they don't feel safe. Because of everything that happens in Europe, including in Italy. These people are incarcerated in detention camps. These people are in jail. Just like me and my friend, we have lived in Italian jails because we drove boats, so we were incarcerated because of that. Within these camps, we lived in inhuman conditions. So we want to fight so that other people don't have to live the horrible experiences we had to endure. So we are trying to find lawyers who give legal support to them. We help them write letters. We go to these detention centers to ask them how they are feeling. We bring clothes to them. We ask them how they're feeling and we try to give them both legal and human support. When we arrived here, we had no choice. We had no choice to be either here or there. For this reason, we decided to create this group to offer our support to those people in need. So we agree these detention camps should be abolished. When we were in the camps, the situation was inhumane. It went against human dignity. It's like being in jail and you are treated violently, both physically and mentally. So these people are deprived of their humanity. Through our experience, we lived the fact and we witnessed the fact that these jails are useless. We are not illegal immigrants. We are not criminals. We're just people who are looking for a better life. But in Europe, no one gives us the permission to live our lives. The detention camps or the camps that are created for blocking the rights of these people are absurd. We want to say stop it. It makes no sense. It's useless. So we're here to listen to all of you, to learn from your experience, to have more material in order to keep on fighting. It's a war we're not fighting with weapons, but with passion. So we want to share our passion in this fight and we want to keep fighting with brothers and sisters who are in a very difficult situation. We will keep on fighting. We will keep on looking for solutions and we will keep on looking for good ideas. Dear colleagues, dear friends, please keep listening to us. Please keep supporting those people who are enduring this situation. We were called smugglers, but we were not smugglers. We were just trying to reach Italy to get to a better life. So let's keep on fighting. Let's keep on listening to each other. Let's keep on participating and being activists because this fight seems never-ending, but we have to keep on fighting it. Thank you very much for inviting us. We're super happy to be here to share these moments with you. Thank you very much.

FRANCESCA: Thank you, Cheikh and Madieye. Thank you so much for the power of your words and for the strength and courage you are sharing with us, that inspire us. So I would like to invite our third speaker, Gee. Gee is the co-director of AVID, Associations of Visitors to Immigration Detainees, a network organization supporting visitors to people held in detention in the UK. Gee has a personal experience of being detained in the UK. After his release, he set up a visitor group to reach out to others inside. Thank you very much, Gee, for being with us. The floor is yours.

GEE: Thank you, Francesca, and also thank you for all of the other speakers who came before me. I was in and out of the room and I'm having technical issues and also other urgent things in the background. So I hope I don't get cut off while I'm speaking. Thank you for having me and it's great to see all of you here from different countries and different continents as well. I've been listening to the previous speakers and their contributions and sort of found myself revising my thoughts and building on the insight that's been shared. I could easily say similar things despite the fact that we're in different countries and also coming from different people as well. I'm just amazed by how this is globalized. I also wanted to take a slightly different perspective today on what does abolition mean to me as someone who has lived through immigration detention, works in a traditional NGO sector that is - let's be honest - not an abolitionist space at all. And our organization definitely do not call ourselves abolitionists or come across because we still have to work around or work with the Home Office that's a border force for the UK context. I also wanted to take a moment to offer an observational perspective as an immigrant to this country, watching and experiencing these systems of control and then reflecting on them. I always find myself like I'm on my two legs on two different boats. I'm an abolitionist through and through. Why wouldn't I be going through the system? But at the same time, I broke a cycle to get to work in an NGO sector where I've been working for the last eight years, actually ten years now. Quite often it's easy to lose sight and it's easy to forget your own experiences and start to repeat almost like a robot on why we wanted to reform or tweak the system. And it's actually a hard space to work in and not sure why I've lasted this long and I'm not going to last any, probably one or two years more. But let me start by saying this, what my observation about abolitionists is in the UK context is.

Abolition is a dirty word. It's a word that people associate with radicalism and unrest and it's a word for troublemakers, for those who don't compromise or toe the line. It's a word for those who disturb the peace of the business as usual. And when you combine abolition with the immigration system, you get something that will never be spoken in the halls of parliament or courts even, and the majority of the NGO coalition doesn't speak of it. It's nearly heard of. And we just never wanted to say or acknowledge that. Well, why is it seen as a dirty word? The question I sort of come back to as an observationalist because abolitionists in the end of the day is forged in an anti-racist ideals and it does challenge the comfort zones of powers and most importantly imagines a future that is uncontrolled and unregulated by systems of oppressions. Something that many people, especially those in position of authority, find it really difficult, even threatening to envision that. It's a word no politician will bravely utter in the UK parliament and that's why it's become uncomfortable even within the NGO world. Rather than calling for eradication of detention, the organisations and many of the activists sort of conformed as a community too often leans towards moderation instead of demanding the end of these violent systems. We see a push for so-called reforms, the removal of children from detention, for example, or the implementation of alternative detention, which in many cases these alternatives are just often detention by other name or alternative to liberty. And for me, it's like abolishing challenges us to go further and it calls us to reject the compromises that keeps the systems of control and punishment alive. And it's also refusal to settle for better when we know the system itself is the road to its core. And that's uncomfortable for many and it's easier to ask for more humane treatment within the system than to challenge the system’s very existence. Because we sort of conform to that. And the issue is that this is almost like a distant dream for a better future and we should be about thinking about the demand for the present and I think that's where the abolition means understanding that these systems aren't broken. Like the callouts of the time in the UK in many politicians before Labour governments, Labour party comes to power, they would keep calling it “conservatives broke the system, they broke the asylum system or the detention system”. And then now they are in power, they keep saying the same thing, “they've broken the system or the asylum system is broken”. And you could easily see the mirror that the media, but also the bigger and wider NGO sector sphere, just copy those words and say, “you know, the system is broken. So we should be fixing it”. For me, it's like this is not broken. It's exactly function as it is designed to. It's to control, to isolate and dehumanize. And immigration detention in the UK is a stark example of this so-called broken system. These spaces are not really merely flawed or in need of repair. They're inherently violent, rooted in racism and built on permits that certain people don't deserve freedom, that they can be locked away, hidden and stripped of their dignity.

Abolition means that retreating into the ocean and it means refusing to accept the idea that any human being should be detained based on their immigration status. So when we do call for abolition, we are calling for something radical, but it's also deeply human. That's what I feel like as a person with lived experience of detention. And it's rightfully free from fear and incarceration simply because you crossed the border to find safety or belonging. And this isn't just theoretical for me. It's deeply personal as someone who has been through the system, I first hand witnessed and seen the weight of the dehumanization and immigration detention. It's a brutal tool that rips people from their community and erases them from public consciousness. And I know what it feels like to have your liberty stolen. And I've been looking at it for so many times with others of my friends who are currently in detention and who have gone before me. And to be reduced to a number and to feel like your existence is an inconvenience to the state, which makes it a really effective tool to make you stigmatized and feel that as an asylum seeker, you're doing something wrong. I remember coming out of detention and making up stories that I was in London on a holiday or when someone would come back on roads and say, "Oh, I haven't seen you for two months and where were you?" And it's that stigmatization. I'd done something wrong. I was a criminal. I wanted to make up a different story. And also in terms of the abolition, it's a tough sell as well in context where so many of us, even in the progressive circles, we call ourselves, we have internalized the logic of detention. When we demand to completely dismantle the systems, we are often met with skepticism. People want solutions, but they want them to fit within the existing framework of the state. This is why it's all interconnected. Quite often I get to have this discussion and I quite often met with some surprise comments like, "What about dangerous people?" You know, when we are talking about endangering, what about dangerous people? “Where would we put them instead?” The assumption behind these questions is that detention is somehow necessary. But that also comes from this area where it is quite bad, but it's necessary. It's worse. It's dehumanizing, but it's necessary. There's a deep fear of unknown where we talk about abolition as well when we are talking about ending detention. People ask, "If not detention, then what? And if not deportation, then how?" It's quite an existential question. But to that I say the real question should be, "Why are we so committed to a system that we know only causes harm? And why are we also so willing to tweak it to make it look nicer rather than to dismantle it entirely?"

But that just precisely is a problem where we've been conditioned to believe that locking people up is the only solution. And including my organization falls for that. Abolitionists and many of the even abolitionist organizations and activists fall for these issues where we always think about it's about closing down detention centers. It's what abolition means. It's about fighting. But it should be about fighting for our collective liberations. This means understanding that immigration detention is part of a much larger system of state violence and control. And the same logic that blocks people in detention centers also fuels mass incarcerations, deportations, and criminalization of Black and brown people in communities across the world. Our struggles are interconnected and abolition is not just about tearing down the system or oppression. It's also about building up a world where humanity and human dignity is non-negotiable. It's about constructing a system that sees people as worthy of respect, safety, and freedom, not just problems to be managed. That's the core of the issue here when we're talking about ending detention. And in the context of the UK, this mindset is pervasive and even those who understand the harm of detention often fall back to reforms just suggesting that we make these spaces more humane or better conditions. And you can't really simply humanize a fundamentally inhumane system. And you can't put up a fresh paint on the walls and it doesn't change the fact that detention exists to isolate and dehumanize. You can't humanize a system designed to crush the human spirit. So this brings me to sort of a tension between reform and abolition. And it's the tension that I feel deeply because on one hand we can't ignore the immediate needs of people trapped in detention. But I've been in those spaces. I know the urgent need for better health care, access to legal advice and basic dignity, but these reforms are necessary to relieve immediate suffering. And I do support them in some sense, but we can't stop there because when we do focus only on reforms, we risk losing the sight of the bigger pictures. Because it keeps the system alive and the system remains intact and it's even slightly softened around the edges. That's why abolition is essential and why we need to talk more about ending detention. And we must resist the temptation of settle for small improvements when we need to. It's a total transformation. I think we should take a different lens to see both of these works as actively disrupting detention. Questions are like, how is your work providing legal advice disrupting the deportation regime? How is visiting disrupting the isolations? It's a state-sponsored isolation. How does visiting disrupt individual staff's humanitarian ideals so that we make them a little bit more fully human? How does your casework give the Home Office a headache? Or the government a headache? These are about disrupting detention. And reform can make the system more palatable, but it doesn't change its purpose. So more humane detention is still detention.

TERESA: I'm really sorry. You have to bring it to a close. It's super interesting, but it's just about getting everyone the same time.

GEE: Sorry. I think I could close it there. That's all I think I've said.

FRANCESCA Okay, thank you. Thank you so much, Gee. That was really, really, really important. So let's go to our last speaker, Steve. Steve is an activist with Castaway Souls of Europe, who are engaged in the struggles of migration, forced detention and forced deportation. He's an independent academic with the Silent University Hamburg, and a radio host with FSK Radio. Steve, the floor is yours.

STEVE: Yeah, thank you very much. First of all, I want to say thank you for the host who hosted us. And I also want to say thank you to my previous speakers. Just after hearing some of you, I really think my notes on my speech that I wrote, I kind of have to throw that in the garbage. And just maybe pick some things from it. So speaking from my experience, I always say I do not want to focus on the adverse effects of my detention or my journey through this impossible system. And then through that, questioning what abolition means to me, like one of these previous speakers mentioned, abolition to me is internalized, to many extents, not by choice. I do not wish to be in this full-time struggle. Neither do I wish to be the oppressor. So on the other hand, I would wish, through my work, individual, collective, that we can build something in between. Something that is not the idea of the oppressor and not really trying to build a future through the suffering of the misery of people. That being said, abolition to me and to those who are like me is fundamental in our life, in our struggle. And our struggle is to fundamentally destroy this destructive genocidal system of the West. Now, before I continue, every time when I speak, some people take offense from it. I do not intend to offend anyone and I do not intend to insult anyone. But mainly, tell a story or speak from the experiences which I have inherited, like I said, not by choice.

Abolition to me means decolonizing and humanizing the colonized, first and foremost. Abolition to me then means dismantling and at the same time decolonizing, humanizing the the Global North. We might sit here and talk about what we should reform, how we should reform. For those people from my positions, we are no longer interested in reforms. For those who want, to whom abolition means something in their life, they no longer talk about reforms. What we need is the discussion of something in between to dismantle the way of life, the so-called way of life that we have in the Global North. So that in a sense means to me abolition is to dismantle borders, dismantle the deportation regime, to dismantle the criminalization of migrants, to educate and to decolonize. So in my struggle and the struggle of people like me, like the previous speaker has said, of some of my previous speakers, I've actually mentioned that this, our struggle is to humanize ourselves and to humanize - to come back to reality what it means to be human. And that is why I said to humanize the West, to humanize the systems that have displaced us, that have killed us, that have stolen our dreams, that have taken our rights away.

We are not proud to have been in these centers, in these detentions, in these prisons. We are not proud, but we take a lot of courage from it that we survived. So when we think about, when we are talking about abolition, we are talking about something that is very, very fundamental in our life, that we want to be changed for us to be able to have the possibility to live, to have the rights, to be able to have rights, to live as human. We do not, no longer intend for the capitalist state, for the colonial states that has brought us to where we are today, we are no longer interested in entertaining the topics, the conversations, about the reforms that is going to make it possible for them to continue to make the laws that they make, for them to continue the practices that they continued all along, for centuries now.

My previous speaker talked about being criminalized as a boat driver, as a smuggler. We use this language, those who smuggle from us, those who extract, those who steal, call us the ones who are stealing from them. So fundamentally, abolition to me means to dismantle this system, to change the narrative, to humanize those who they call the unwanted in this part of the world. And we are going to do, because my life commitments, not by choice, like I said from the beginning, my life commitment has been, will be, to dismantle, to help those who are like me. And together with those who are from the West, who want to work together to dismantle the system, to work together with us to create something new. So in my opinion, even though we don't use the word abolition like Gee said, in this part of the world, it's associated with a lot of negative things. But we embody in everything we do, in everything we advocate for, in everything we struggle against, is to dismantle this very system. And that for us, with allies who want to, in reality, work towards a humanistic idea, or another idea that is humanistic, it is not in any way possible talking about coexisting with oppression, that go hand in hand with oppression. We are campaigning that these people, that people like this, like you, me, can look at us, ourselves, tomorrow and call ourselves human patriots. And that in itself is what we need. Maybe not to call ourselves abolitionists, maybe not to call ourselves anything else in order to fit, but to do things in the everyday life so that we see changes, that we go away from the narrative that we've been taught, that we've been indoctrinated, that supports the system, that the system benefits from, but to create something new. And those things that are new, something different, we see it every day, because we see these different organizations, the different people, these different struggles, who are trying to create something new. What we are urging is to work together to create something new, to abolish, because we are done with reform. In 2015, I give that as a little story. Many of you will remember, there was the little boy who drowned, during the so-called summer of migration in Europe. And in 2015, at the same time, there was the whole new reform against migration. And a lot of us, like Gee said earlier, will support this, because we so believe that we need to have borders, but we forget that borders are unnatural, that these are man-made. And we need to come back to humanizing ourselves again, and doing things differently. And I'm sorry my time is up, and hopefully I can express myself much better later.

FRANCESCA: Thank you. Thank you so much, Steve. And thank you to all the speakers, for sharing their experiences, their struggles, their insights. It was mind-blowing to listen to you all, and so, so very inspiring. I think there's so much to think about. And I'm sure, I mean, we'll continue to build on this inspiration and these insights in the second part of the workshop. So now let's take five minutes break, and then we invite people to move to their breakout rooms. And we'll give some more instructions. So please remain here. We'll just, you know, have a break to breathe and stretch a bit. See you.