The Bank and The Mayor’s Office Won’t Give us our Freedom

by Lola Olufemi

Green square with the words ‘Lola on Advertising Tube Safety’ in light orange text with some graphic design

1. In June 2020, police officers Deniz Jaffer and Jamie Lewis take photographs of the dead bodies of Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry, Lewis superimposes his face onto one of the pictures of the women’s bodies and Jaffer shares multiple images in a Covid WhatsApp group. In May 2021, Sarah Everard is murdered by sitting police officer Wayne Couzens. In the same month, the government introduces the Police Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, which extends police power to detain, arrest, surveil and control protest. The Bill increases conditions related to the ‘disruption to the life of the community,’ enabling police more power to control the size, movement and noise of protests whether static or moving, concerning one person or multiple people. The introduction of Serious Violence Reduction Orders (modelled on the Prevent Duty) as well as Serious Violence Duties removes the need for reasonable ground for police stop and searches, enables punitive measures to be imposed on those who “ought to have known” that another person carrying a weapon would commit an offence and requires local authorities to hand over information about individuals, patients and clients to police.

2. She could be anyone. Variously named Zarah, Sarah or Jane in VAWG sector reports, she makes up the one in six women in the United Kingdom who have experienced financial coercion or abuse in a current or former relationship. This looks like credit cards being created in her name, being forced to take on the debt of a partner, the threat or actual withdrawal of food or other necessities. An allowance to spend on certain items controlled by a partner. Sometimes it is not enough to feed herself and the baby and so on many nights she goes hungry. She cannot leave. She has nowhere to go.

Feminism is a political methodology that can help us name the structural, interpersonal and otherwise murky forces which make up a social landscape. It does so by enabling an examination and analysis of the material conditions which underpin social organisation, it helps us understand the ways that capitalism’s operation is specifically gendered and racialised in its arrangement of labour, social relationships, the economy as well as prisons and the police. In trying to define their method, the way they would go about arriving at his political conclusions, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote,

“The premises from which we begin are not arbitrary ones, not dogmas, but real premises… They are real individuals, their activity and the material conditions under which they live, both those which they find already existing and those produced by their activity.”

Our material conditions consist of the means and resources we use to produce our subsistence and the power structures, relationships between people, norms and behaviours that determine that production. Feminism should help us think about the processes, means, activities that go into creating people and daily life in any given society. Jennifer Wicke notes that a materialist feminist approach,

argues that material conditions of all sorts play a vital role in the social production of gender and assays the different ways in which women collaborate and participate in these productions.

How are material conditions crucial in the production of gender? How does the way we live, all the resources that we do or do not have access to, produce our understandings of ourselves, others and perhaps most importantly, the violence we experience? For abolitionists, these questions are crucial because abolitionists often make direct links between the quality of one’s material conditions and the criminalisation of certain activities. They attempt to uncover why it is that certain activities related to subsistence are often criminalised, how, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues, prisons became the answer to social problems. If you are a mother whose state benefits have been cut, and you cannot afford to feed your child and so you steal baby formula from Tesco, you do so because a basic need (the need to eat) is not being met by your material conditions. We know for example, that a majority of women in prison have experienced domestic or sexual violence and one study of men in imprisoned in HM Prison Parc found that 84% of male prisons reported being exposed to childhood ‘adversity’ or abuse. In these instances, it is the basic need for nurturing, sustaining and caring relationships which provide comfort, safety and stability at any early age that has not been met. Rather than think of crime as a matter of individual wants, desires and wills, this theoretical framework helps to ground our assessment of violence by asking why certain activities are criminalised, why certain needs are not met and perhaps most crucially, helps us develop political strategies to meet those needs communally as means of initiating societal transformation. It externalises violence, exposing how a violent society produces cycles of harm, it points us towards the exploitation and seizure of resources made permissible by capitalism as the ultimate source of emotional, physic and physical harm to human beings.

If we turn to the question of violence against women, feminists that long argued what traps women into cycles of harm: at the hands of bosses, partners, police officers and strangers is the way their subjugation, in the family structure, in the workplace, as political subjects in the street, in their interpersonal relationships are sown into the fabric of their material conditions. A migrant worker with no recourse to public funds cannot demand better working conditions from her boss; a sex worker, whose work is criminalised if she refuses to work alone cannot protect herself from violent clients; a woman experiencing financial abuse cannot leave if all the domestic violence shelters around her have shut down due to funding cuts. The most vulnerable often do not have access to the resources that would enable them to escape violent situations because resources have been withheld from them through the slow concentration of wealth from the working class upwards, a process managed by the state. We know that the history of capitalism’s formation is plagued by stratifications in society. In her book, The Intimacies of Four Continents, Academic Lisa Lowe writes that “capitalism exploits through culturally and socially constructed differences such as race, gender, region, and nationality and is lived through those uneven formations” and so, experiences of cycles of harm by women are lived differently, inflected through race and other vectors, leaving racialised women, disabled women, migrants, anyone whose labour powers the dark underbelly of capitalist production, the furthest from the resources they need to survive.

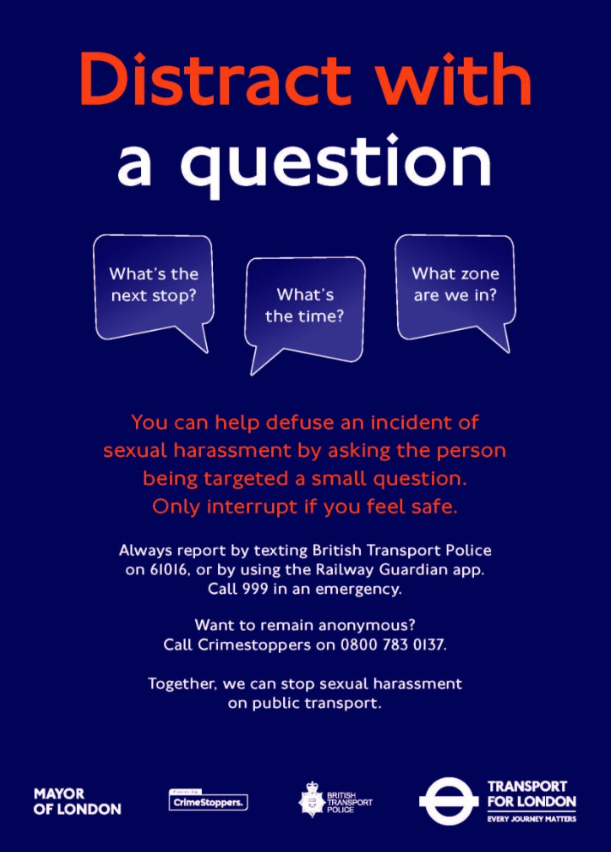

We can use a materialist feminist method to analyse these campaigns and identify the gap between the state’s promises and priorities and the actual violence in the form of harassment, stalking and abuse experienced disproportionately by women across the United Kingdom. Feminism reminds me that these adverts are not only reflective of the society I live in (one where gendered violence is an ever-present threat) but they are constitutive of it. They are part of the fabric of a social arrangement in which people’s are continually required to invest in the belief that the TFL or the bank truly cares about them, that the Metropolitan Police want their safety, or that a few feeble tips on bystander intervention are enough to seriously challenge the culture of violence that kills women in their homes, incarcerates them if they defend themselves and enables them to be mocked by police officers in their death. Trying to understand how and why these instances are connected means tracing the decline of material conditions in the United Kingdom. This brings us back to the devastating effects of neoliberalism which, in the last two decades alone, have produced a social landscape in which the welfare benefits once provided by the state: legal aid, social housing, Personal Independence Payment, domestic violence shelters, child tax credits, educational maintenance allowance, have either disappeared or been reformed to decrease access to them whilst the apparatuses of criminalisation have been fortified and expanded. Most recently, in their “Plan for Change” the new Labour government under Keir Starmer has promised 2.3 billion towards prison builds over the next two years, with the aim of establishing 14,000 places by 2031.

To understand the anti-harassment campaign as a representative function of the decline in material conditions, we must study the effects of neoliberalism not only on the economy but on people and social relationships. Post-war Britain was partly characterised by reforms related to health and education, the construction of a social welfare system which was powered by labour from those from the former colonies. Until the mid-1970s, successive Labour Governments pursued economic and social policies favourable to Trade Unions, which translated to a rise in living standards and forms of voluntary wage control. The social effects of such policies produced somewhat meaningful reliance on the state to reach subsistence, the notion that education and health as basic needs, should be free and accessible. (These resources were of course, unevenly distributed, in 1962, the Commonwealth Immigrant Act placed stringent and draconian restrictions on the ability of Commonwealth Citizens to migrate to the United Kingdom). The breakdown of this socialist contract by the Labour government and the introduction of neoliberalism in the form of privatisation and increasing financialisation from 1979 onwards under Margaret Thatcher changed not only the structure of the economy but social relations. In Feminism Interrupted, I defined neoliberalism as,

the imposition of cultural and economic policies and practices by NGOs and governments in the last three to four decades that have resulted in the extraction and redistribution of public resources from the working class upwards, decimated infrastructures of social care through austerity measures privatised the welfare state and individualised the ways we relate to one another.

Neoliberalism was and is specifically gendered in its application, austerity measures implemented from 2010 in order to “balance the budget” hit women, who are more likely to be in low wage work and having multiple dependents, the hardest. When feminists argue that the gender is produced through the relations that structure material conditions, they are arguing that is the structure of labour, work and the economy that often determine their fates. A society which is built fundamentally on the exploitation of many for the benefit of those who retain ownership of resource can never and will never end gendered violence, precisely because it depends on that violence to function. It needs gig-economy precarity that women are overwhelmingly concentrated in, poorly paid cleaning and childcare work for example, in order to thrive. The social doctrine of neoliberalism, when first introduced in the late 1970s, argued that rather than rely on state benefits or welfare, one must depend on themselves, their own ingenuity and their work in order to survive. The legacies of this political mandate expressed in austerity cuts slashed through what remained of the welfare state, plunging thousands into precarity. In 1987, Margaret Thatcher famously declared ‘Who is society? There is no such thing!’ ushering an anti-communalism which no doubt has shaped approaches to prisons, policing and violence; if there is no communal answer to violence, no such thing as society, then support for expansion of carceral systems as an effective deterrent persists.

Advert with image of a hand and puppet strings on a tiled wall, by HSBC which says ‘When an abuser controls your finances, they control you’

When I get on the tube and see HSBC attempting to raise awareness about financial abuse or encouragement from the Metropolitan police to report instances of harassment, I think about how our welfare system has been deliberately dismantled in the last decade and a half. The fact that this knowledge has been outsourced to a financial company indicates the non-existence of state structures that could provide a material change in the lives of working-class women through resource. I think that the privatisation of our everyday lives is complete. I do not think that HSBC, whose incentive is the accumulation of wealth and whose wealth is acquired through violent means, cares about the fates of women across the country but that there is capital to be made, consent to be manufactured through the appearance of this help. As feminist direct action group Sisters Uncut have always maintained, women need safe routes for escaping violent situations. A bank will ever give that to them, no matter how much it claims it wants to.

Similarly, the collusion with policing institutions to tackle sexual harassment, as with TFL and the Metropolitan Police, results in increased instances of criminalisation of the poor, which we know will not end sexual violence because we are most likely to experience sexual violence at the hands of someone we know. Often violence against racialised working class people and those in mental distress on the public transport is justified and encouraged because they are deemed a “threat” to those around them. The case of Jordan Neely, who was choked to death by Daniel Penny on a New York subway line is one recent example. Whilst bystander intervention, shutting down harm when and where we see it is crucial, when these solidaristic actions are advertised by the state they lose their radical potential because they become attached to the incentive for individuals to “report” instances of harassment, reanimating the process of criminalisation. Emphasis on reporting instances of violence to institutional bodies legitimises their position as the only viable recourse for recognition and accountability after violence is experienced. Yet the opposite is true. In the case of sexual violence and harassment, charging and conviction rates for sexual violence are lower than 2.7%in England and Wales. In other words, the police rarely provide an adequate or satisfactory response to sexual violence.

In 2023, over 1,500 police officers were themselves accused of violence against women in a six month period. What good is reporting violence to an institution that enables it? In the wake of Sarah Everard’s murder, police brutalised several protestors at her vigil. This show of force was a watershed moment for a new generation: more women are rejecting the ‘bad apples’ narrative put forward to policing institutions, recognising that the very function of policing places them in danger. Research, lived experience and materialist analysis reveal to us that: accessible public transport, community-based night-time safety programmes, staff member training, expansion of socially reproductive labour beyond the family, travelling in groups, decriminalisation of sex work, harm reduction programmes, non-police associated crisis intervention, strong trade union affiliations political education are all tools which could lessen instances of sexual harassment and violence in the home, in the workplace and on the street. When we are cat-called or groped, many of us run to our networks of family and friends who can provide us a place to process our emotions and hold negative feelings because we know a police report, filed and never followed up, cannot do this for us. The false promises from a state that continues to abandon the working classes, shifting its responsibility to care for them on to NGOS, charities and corporate entities through what academic Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “organised abandonment” will never improve our material conditions, The era of policing via consent, what Aviah Day and Shanice McBean describe as ‘“developing positive relationships with members of the public; and securing the willing participation of the public in the work of maintaining law and order” is slowly being eroded.

Our society is invested in ‘solutions’ to violence that do not prevent more violence from occurring. What a materialist feminist approach enables us to understand is this investment is intimately connected to the devastating effects of neoliberal austerity which continue to ruin lines. As more and more resources are stripped away from us by the state, the possibility of ending violence by meeting people’s material needs lessens and patterns of increased criminalisation emerge. Criminalisation emerges as a governmental response to unmet needs. These twin processes of state neglect and criminalisation are features of what a number of abolitionist scholars call a “carceral geography” with concerns the experiences and relationships that define a punitive social landscape, space-making as human activity, spatial makeup of sites of imprisonment and the penal mechanisms of control employed by governments and authorities. Neoliberalism emboldens the institutions of prisons and policing through a focus on the individual offender, ‘crime’ as a personal and/or moral failing rather than a social reckoning, using prisons as the sole answer to problems that are social and collective in nature.

We must also connect the existence of anti-harassment campaign to the real lives of the women the state has imprisoned, who are themselves often victims of sexual or domestic violence. Why is the state, TFL and the Metropolitan Police permitted to educate the public on bystander invention and then criminalise the women who fight back against their attackers, as is the case of Kiranjit Ahluwalia, Rebecca Searing, Siyanda Mngaza, Sara Thornton and Sally Challen? Why should women trust the police, when the recent undercover policing inquiry has revealed how they routinely infiltrated activist groups, spying and sometimes forming relationships with members of over 1000 political groups from 1968-2010? What good is anti-harassment campaign if it refuses to understand the root causes of gendered domination? Abolitionists find answers to these questions through concerted efforts to improve material conditions and reestablish the communality central to rethinking, critiquing and abolishing concepts of innocence, safety and criminalisation. By questioning the premise that police and prisons keep us safe, we always arrive, back at the networks of human interdependence that sustain us in urgent moments. “We keep each other safe,” we do so by refusing to contribute to the criminalisation of those fighting to subsist, by focusing on building institutional and interpersonal structures of care which prevent cycles of harm from occurring, by refusing complicity in genocide and imperialist violence committed in our names. By ensuring that every human being has access to nutritious food, community, housing, the ability to learn, change and grow without being exploited. Whether located inside a trade union, domestic violence shelter, mutual aid network, food bank, in schools – feminists in these arenas contribute to the abolitionist struggle daily by refocusing attention on the necessity to divorce organised abandonment (state neglect) from organised violence (police, prisons and other carceral apparatuses) by helping build the connections between the production of gender through social relationships and the unequal power relations that feed the class system. In their book, Abolition Revolution, Shanice McBean and Aviah Day, founding members of Sisters Uncut, note

“A revolutionary abolitionist approach… would demand we democratise public funding allocation at the community level, redefine the parameters and definitions of crime, design institutions that exist solely to respond to the needs of ordinary people and redistribute funds not just at the level of public services, but from the wealthy to the global poor in order to tackle the root causes of harm. Abolition must orientate our work towards a future run by people, for people, and not by profit, for profit: this is revolutionary abolitionism.”

Vesting power back from the state in order to initiate processes of redistribution requires us to recognise abolition as a life-long commitment with no easy solutions, one fundamentally rooted in the knowledge that despite their promises, the police or the bank can never and will never grant us our freedom.